Article originally published in the Daily Hive.

“Just because something is traditional is no reason to do it, of course.”

This sentiment was written by beloved children’s author Daniel Handler, more widely known by his pen name Lemony Snicket. It has also become the centre of a culture war that has taken root in Calgary over a controversial part of the city’s most famous event: the Calgary Stampede’s rodeo and chuckwagon races.

The Stampede plays host to some of the city’s most iconic attractions, showcasing Calgary’s vibrant culture and arts scene. Sadly, the celebratory mood is soured by a few outdated and cruel events.

Cowboy culture takes root in rodeo

When the first rodeo took place at the Calgary Stampede in 1912, the romanticized image of cowboy culture was fresh in the minds of North Americans. In actuality, open-range cattle ranchers were an American import and were only common in Canada from the late 1870s to the early 20th century.

Though the movement certainly didn’t define a large part of our nation’s history, the romantic idea of cowboys was married with the draw of the agricultural fair to present rodeo for entertainment purposes.

The public was once captivated by the fast pace of rodeo, which involves animals being agitated with tools like uncomfortable flank straps or practices like ear pulling and tail twisting. These methods provoke the animals’ “fight or flight” fear response, leading to bulls and horses bucking or calves and steers bursting out of the chute to be chased and roped or wrestled to the ground.

But times have changed; the public expects better for animals.

Rodeo falls behind public’s welfare expectations

Unlike the requirements for on-farm handling of the same animals, the practices used in rodeo have failed to evolve with changing public attitudes. Canadians have greater expectations of transparency and humane treatment of animals on farms. The National Farm Animal Care Council’s Beef Cattle Code of Practice, which provides guidelines for the care and handling of beef cattle in Canada, requires “quiet handling techniques” to be used.

Quiet handling would make many rodeo events impossible, but animals are paying the price for the continued use of stressful methods and fast-paced events. The Stampede sees near-annual animal deaths in the rodeo and chucks.

Near-annual animal deaths a stain on celebrations

Since 2000, there have only been three years of the Stampede in which no fatalities were reported: 2003, 2016, and 2021. The Stampede’s deadliest event, chuckwagon racing, was cancelled in 2021 due to pandemic concerns.

In total, 105 animals have died at the Stampede since the Vancouver Humane Society began tracking fatalities in 1986, including 75 horses used in the chuckwagon races.

These high-profile deaths, along with a growing body of evidence showing that animals experience stress, fear, and pain in rodeo events, are changing the hearts and minds of the public.

Polling reflects changing opinions

A Research Co. poll conducted in February this year shows that more than half of Albertans disagree with the use of animals in steer wrestling, calf roping, and bronc riding. When presented with photos of calf roping, 60% of Albertans and 62% of Calgarians said they would not watch the event.

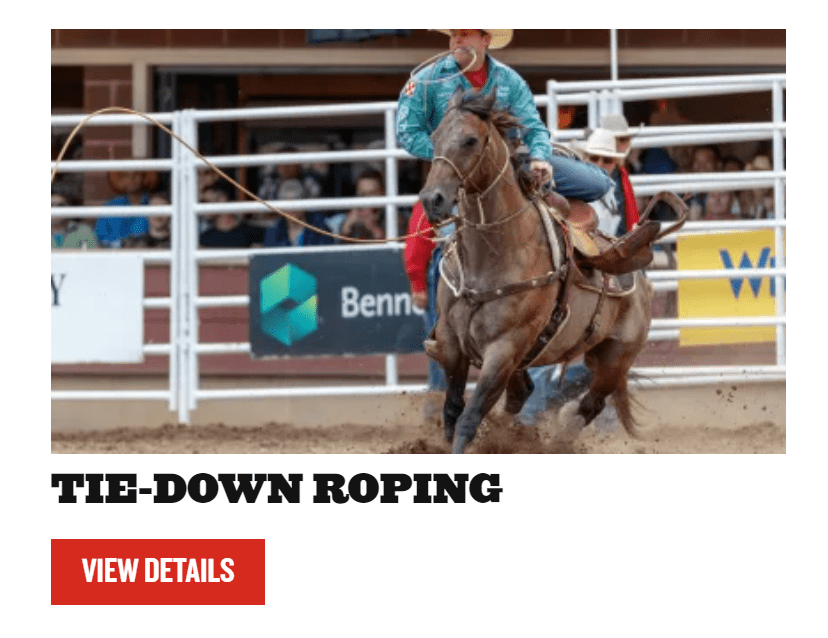

Evidently, the look of fear in the eyes of a calf as he is chased, thrown to the ground, roped, and dragged by his neck while the oblivious contestant walks off celebrating is enough to put most people off the so-called sport. Perhaps this is why the Calgary Stampede website’s depiction of calf roping (euphemistically deemed “tie-down roping”) only features a contestant and horse, with the rope mysteriously disappearing out of frame.

Rodeos losing steam elsewhere

Rodeo’s dwindling popularity is already making waves elsewhere. Last year, the City of Red Deer bade farewell to the Canadian Finals Rodeo after four of its five years of hosting resulted in financial loss.

Many cities across North America and nations across the globe have banned rodeos, limited events, or prohibited tools such as electric prods, flank straps, and sharpened spurs, which are used before and during events to control animals or provoke desired behaviours. These include Vancouver, British Columbia; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; New York, New York; Los Angeles, California; parts of Brazil; the United Kingdom; and the Netherlands.

Increasingly, public values are leading a change in the way we view the use of animals in entertainment. Rodeo is becoming a symbol of outdated cruelty, much like the once-popular use of performing animals in circus acts or dolphins trained to jump through hoops in aquarium shows.

The future of the Calgary Stampede

Surely Stampede organizers are aware that they must adapt to changing interests and attitudes. The “Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth” would not have survived more than a century if it insisted on staying the same.

The Stampede has evolved to grow its Midway into the sprawling icon it is today. It has added new exciting exhibits and events, including a host of concerts that draw hundreds of thousands of spectators each year. Yet, in its animal events, the Stampede remains stuck in the past. It has become a symbol of stagnancy and division rather than progress and unity.

If the Calgary Stampede is looking to the future, one thing is certain: cruelty has no place there.