Have you shopped at a vegan business recently?

As consumers, we have the power to make compassionate choices that align with our values. More people are choosing animal-free products and services and helping to reduce the demand for industries that exploit animals. Meanwhile, vegan businesses are on the rise to meet the demand for a kinder, more ethical marketplace.

In this month’s episode of The Informed Animal Ally, Kyla and Audrey from Vegan Supply and Paula from Compassion Ink Studio share perspectives on operating a vegan business.

Vegan Supply

Kyla: Hello, this is Kyla and Audrey from Vegan Supply.

Kyla: My name is Kyla and I am the executive assistant to our lovely owner and founder, Jason Antony. And with me is Audrey.

Audrey: Hi. I’m Audrey. I’m the operations manager here at Vegan Supply, overseeing two physical retail stores, our e-commerce business, as well as the distribution side where we sell to other businesses.

Kyla: Audrey is definitely hands on and can speak a lot about successes, challenges, opportunities within the business. And I can more speak to Jason’s side of things. So Audrey, what have you found to be a success?

Audrey: I think definitely a highlight for me is being able to offer vegan solutions to people who might not otherwise have them.

Whether that’s offering products that they don’t have access to where they’re from, on the e-commerce side of things, where we’re able to ship all over, or even just having unique solutions that somebody coming in our store who never heard of soy curls before, and how can they cook with them and how is that a great substitute for their protein and really being a bridge to get people to think differently and help them in their vegan journey if they’re on one, or even just if they’re vegan curious and want to learn a little bit more.

Kyla: And it is something to be said that with this business, we have the means to get anybody vegan products, literally anywhere in the world, which is a really great thing to be able to do.

Audrey: Absolutely. And also working with bringing really exciting and new innovative products to market.

Some of my favorites from this year that we’ve brought in are Juicy Marbles and Yo Egg.

I think when I first went vegan, I didn’t dream of a world where I had a vegan poached egg that actually had a runny yolk. And today is the day that we are able to access that now as vegans. So it’s incredibly exciting.

And Juicy Marbles is another one where it’s a vegan steak. Some of those things that people say like, “Oh, I could never give this up.” There’s a lot of stuff that people don’t have to give up anymore. And it’s because of brands like this doing really cool things in the food science area.

Kyla: That’s right. Yeah. Bridge the gap. We’re here for it.

With all this great stuff though, there are challenges. So what are a few of the challenges that you’ve noticed within the business or being in this space?

Audrey: Yeah, I think so from the start, you know, we’re a vegan business and our name is Vegan Supply.

And there’s a lot of feelings out there in the world to that word vegan. And I think a challenge is overcoming that perception that we are just for vegans because we sell vegan products exclusively. Yes. But our goal is to have more vegan products available, but that could be somebody who is an omnivore looking to reduce meat in their diet or any kind of area like vegan products can be good in and of themselves of their own merit.

Trying to break that barrier while also still holding true to our values is definitely a challenge. I think we start from a little bit of a disadvantage, but it’s just a challenge for us to overcome.

Kyla: Yeah, that’s right. It’s definitely the bias with the word vegan and it is our very name, but we move forth.

So on that note, what is something that you’re looking forward to in the future? Some cool opportunities coming up.

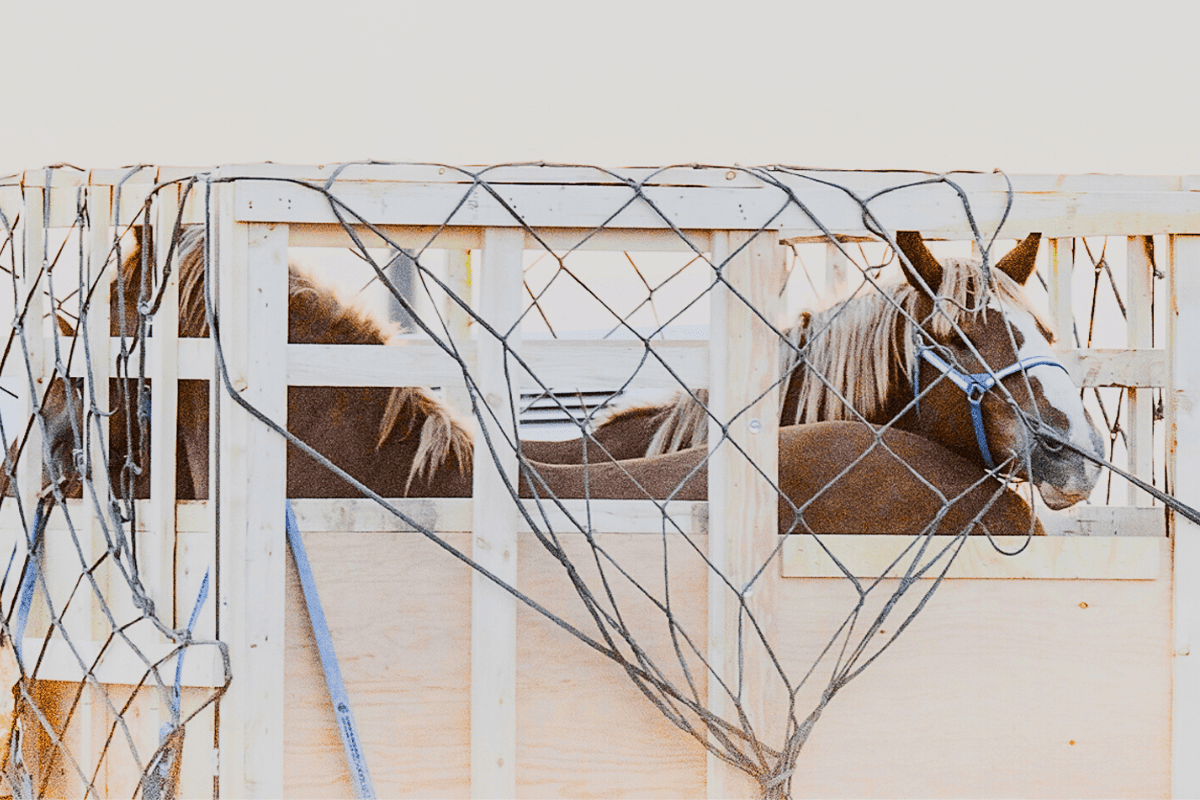

Audrey: Yeah, well, I’m mostly looking forward to being more collaborative with a lot of different organizations. I think in the last few years, we’ve worked a lot with different sanctuaries or different organizations to shed more light on them or collect donations.

And I think we do better as a whole when we lift each other up. So I’m just looking forward to the different partnerships in the community in the coming years.

Kyla: Definitely. I will just do a quick little plug that a few years ago, Audrey and I created a monthly donation program within Vegan Supply, and we feature two sanctuaries, rescues, anywhere that anybody is honestly helping animals.

We will feature you on our website and in-store and raise funds and allow you to keep doing the important work that you do with animals on that note.

If you’re listening and you haven’t been featured, or you know somebody that you would love to see featured, please let us know. Reach out to info at vegansupply.ca.

Any final notes about the world of business and vegan spaces?

Audrey: That we just need to support vegan businesses. I think there are few of us and you know, it’s a cliche, but we vote with our dollars and when we buy a product, we’re telling those businesses that we want to support them. So I think now more than ever, it’s important to support businesses that align with the values that you have.

Kyla: That’s right. Money talks. So let’s use it for good.

Paula: Hey everyone. My name is Paula and I’m a tattoo artist in Burnaby, B.C.

On Instagram, I am @inkbypaula and my tattoo studio name is Compassion Ink Studio.

A little bit about myself. I’ve always been very sensitive person, always been an animal lover. As a child, I loved art class and I loved our family dog or family hamsters and you know, I was that kid, and I still am, like many of us, that person who will pick a worm off the sidewalk to help it across.

In high school, I took home this baby chick that was going to be fed to a snake and ended up rehoming it.

I’ve always been an animal lover, and honestly, it wasn’t until I was an adult that I really started thinking about the impact of my choices on animals.

My partner and I decided to unlearn a lot of the habits that we grew up with, and we started with our diet. A lot of vegans usually start by switching to a plant-based diet.

But we also, beyond our diet, try to divest from animal exploitation. And we know it’s not possible to live a completely harm free life in this society, but we do our best. And I think that’s all we can do.

So when I launched my tattoo business, making it vegan was a no brainer.

People will ask me, you know, what’s a vegan tattoo? What makes it different than a regular tattoo? And, the main difference is that I ensure that every part of the tattoo process is animal-free.

Most tattoo shops nowadays actually use vegan ink, just by default, which is great. But for me, I take it a step further. So for example, the soap I use in my studio will be vegan. The transfer paper that I use is vegan because not all stencil paper is vegan.

My shop doesn’t have leather furniture. I don’t have like animal skulls hanging on the wall or framed dead insects on the wall.

If you’re an animal lover, going to a vegan tattoo artist will sort of ensure, beyond the ink, that your experience is going to be as animal-free as possible.

Another big part of my business is fundraising. I’ve had the privilege of fundraising for animal sanctuaries and fundraising for animal activists and human rights activists as well. It’s really rewarding too be able to offer a service like tattooing that blends art and community and activism, which was really cool.

When I first started tattooing, it actually was the vegan community that really helped me build on my portfolio because the support was there. So as soon as I started tattooing and put out there that I’m a vegan tattoo artist, I had a lot of vegans come and be like, Hey, this is awesome. I want to support you.

I’ve met a lot of incredible people through tattooing. Some tattoo sessions are hours long and we share stories. Being an animal lover is a big part of who I am, so I’m just grateful to be able to share my passions and the things I care about with my clients.

That leads me into the next thing I wanted to bring up, which is, I’ve had people question whether it’s a good idea to bring in my politics and sort of combine it with my business Instagram accounts, you know, posts, not only about tattooing, but posts about the things I care about.

And I think that sure I may lose some clients or followers who don’t align with whatever my stance is. But I also believe that a big part of my success as a vegan business owner comes from me being transparent and sharing what I care about. I think a lot of people nowadays do want to support businesses that align with their worldview.

Despite whatever challenges may also go along with that, I think it’s worth it in the end.

One thing I love with my tattoo business is collaborating with other businesses. So for example, I’ve collaborated with Mila Plant-Based restaurant or Zimt Chocolates. We do this to bring the community together and then donate a portion of proceeds to a cause.

I recently organized a raffle with several vegan businesses to fundraise for two families in need. Collaborating is something I really enjoy. And even collaborating with Vancouver Humane Society to share a little bit about me is such an honour. So thank you for listening and I hope to tattoo you one day.

Next episode

Please join us next month as we discuss common arguments people use to oppose veganism and ways to respond.