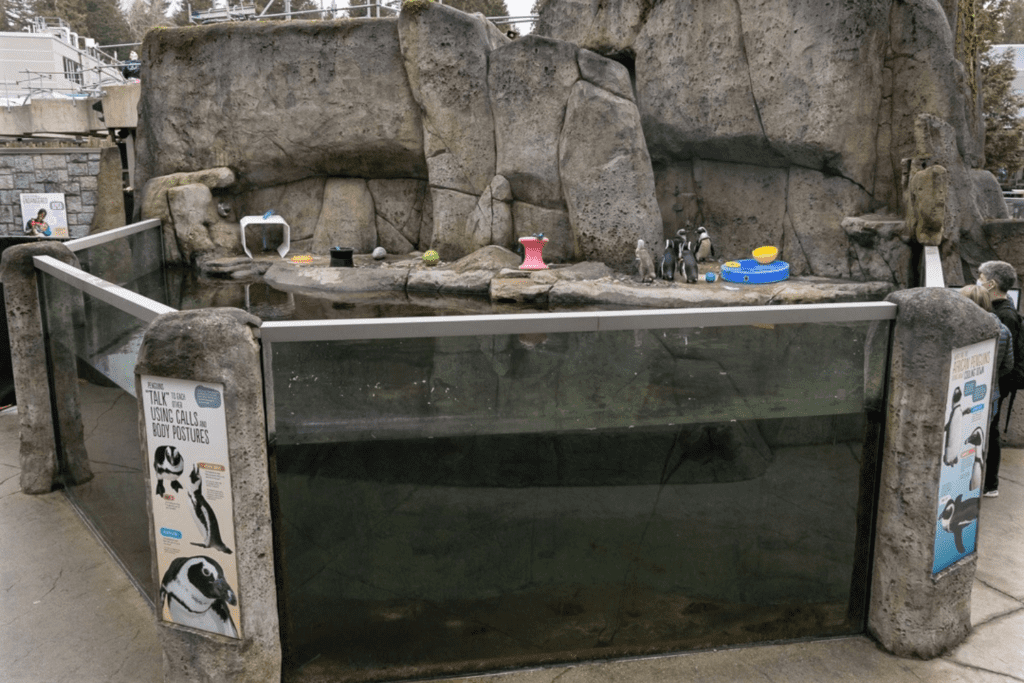

Wild and exotic animals in captivity are confined to spaces thousands of times smaller than their natural home ranges.

Deprived of the ability to exhibit their natural behaviours, many can be seen pacing, licking the bars of their cage, huddling in corners, and languishing in boredom. In this month’s episode of The Informed Animal Ally’s series on animal cruelty, animal advocate, award-winning writer, and Zoocheck founder Rob Laidlaw joins the Vancouver Humane Society’s Amy Morris and Chantelle Archambault to discuss the issues wild animals face in captivity and what can be done to help them.

Note: This written interview has been edited for length.

Featured Guest: Rob Laidlaw

Founder of Zoocheck

Rob has spent more than 40 years working to protect the interests and well-being of animals in Canada and around the world. He is a chartered biologist, founder of the wildlife protection organization Zoocheck, an award-winning author and a winner of the Frederic A. McGrand Lifetime Achievement Award for substantial contributions to animal welfare in Canada.

History of animal advocacy

Amy: Could you share a little bit of your background working with the wildlife and what drew you to this?

Rob: It’s a bit of a long story, but I’ll try to give you the abbreviated version.

When I was a child in public school, I was always the kid that read every book in the library on animals, on conservation, on nature, and all related subject matter. That was sort of the first manifestation of my interest in animals. That dates back as far as I can remember.

I also did something else. I started writing letters. I’d read in some of these books and other materials about these organizations, most of them in Europe, like Beauty Without Cruelty and Compassion in World Farming; some of the groups that have been around for decades and decades. I would write away to them for information about animal issues. I did this for a number of years and continued reading. My interest in animals grew and grew and grew, and I’m also very interested in science.

Then I went to see The Animals Film, which was done by a producer out of New York City. It was the first time on film where you had basically a cataloging of images of what humans do to animals, and some of it was absolutely horrific stuff. And if you remember that, you know when that film started showing the internet wasn’t available, so you couldn’t just get on the internet and see all the stuff that you do today. Animals and farms and laboratories and circuses and all those things. This was all new to people and people actually vomited and left the theater that I saw this in. It had a really profound effect on people.

At the end of this film, they had a group called the Northern Animal Liberation League. It’s a UK group that assembled large groups of people, and they would take photos. That kind of action is in the news just recently here in Canada. I thought that was a very compelling call to action for me.

So when I left the theater, I thought, Okay, I know all this stuff. I’ve been writing about it. I’ve read all these books since I was a kid. I’ve got this good base of knowledge, but that doesn’t help. I’ve got to do something.

So I started looking around for something to do, and there were no advocacy groups, except a few very that had been around for many years where the discussion was at the level of, are we gonna have popcorn at the next fundraiser? It wasn’t about issues.

So I started doing my own investigations into animal abuse, not knowing where they would lead. I did a number of different things. I found a few people; we got a lot of exposes in the newspaper.

And then a fellow came up in the early eighties. He was somebody who had done very large mass events for the peace movement throughout the United States, and he had become interested in animals and he was setting up this organization for one purpose: to one year from that point where he held the first meeting in Toronto, to set up and carry out this very large protest for the annual convention of the American Psychological Association. And it was geared towards protesting the use of animals in certain kinds of psychological research.

We built that organization up in Toronto from nothing to 9,000 members in eight months. We had 300 people a month coming for meetings. We ended up doing rallies with 1,000 or 2,000 people.

In 1984, I came across a zoo in Ontario about two hours from Toronto. It was what you would now call a roadside zoo. I didn’t know those things existed, and I had actually bought the propaganda about zoos. I had a discomfort with them, but I thought generally speaking, they were positives. I didn’t know any better.

I visited this zoo and it was horrendous. The animals were living in excrement, literally a metre or two deep. They had been on it so long and they had compacted it into a concrete-like consistency. The cages looked like they had been banged up by a bunch of kids over the weekend who got scrap materials from the dump. It was a horror story.

I inquired at the admission booth when I left about one particular animal, which was a juvenile black bear that was chained by the neck in a small cage. And I said, “Why is that bear in that circumstance?” And they said, “Oh, don’t worry, it’s just temporary. He’s going down the road to another facility.” Well, I said, “Okay, great.” At least it’s temporary.

I visited the zoo he was going to after I left, and it was worse.

And I thought, I really have to do something about this. I don’t care how long it takes, I’m gonna do it.

I thought naively that what I saw at both those facilities were anomalous. Maybe it had been a situation where thousands of people went there, but everybody thought everybody else had complained when nobody had complained. It was that kind of maybe a weird scenario where it somehow, Didn’t get on the radar of the right people.

I was wrong. I found out that places like that were completely unregulated. Nobody knew what was in them. Nobody knew how many there were or anything else.

My initial estimate of trying to tackle this and deal with it was 18 months. It’s 38 years later now.

I never ever dreamed that it would go beyond roadside zoos in Ontario. Now there’s been projects right across the country in the United States, in Europe, Japan, Pakistan, lots of different activities and an expansion into other areas; particularly in Canada into wildlife management issues.

I’m very stubborn. You know, I’m not an Einstein. I don’t have the money of Bill Gates, but the one thing I think I do have in me is tenacity. I’m gonna stick with this until it’s done. And I can honestly say that from that point way back in the old days, that the landscape of wildlife in captivity issues in Canada is now profoundly different.

I’m not saying it’s all because of me or people I’ve been associated with, but we’ve been there the whole time and we’ve had a finger sort of in most of those pieces of the pie doing things and in helping to do things that are effective. So I think that it was probably a good thing to have that trait in me to never give up.

The other thing that goes along with it is I hate to lose. I remember in the early days many of the zoo people would say, “This won’t change. You’ll be gone long before anything ever changes.” And I thought, No, that’s not the case at all. You’ve got to go into these things believing you can win.

It’s been a long, interesting journey. I’ve met a lot of fantastic people, great activists, seeing what’s going on all over the world. I’m not stopping any time soon.

Animal captivity in Canada

Amy: You mentioned like a few different ways that you’ve encountered wildlife and worked on issues such as roadside zoos, and zoos and aquariums in general. What are some of the other ways that wildlife are kept in captivity in Canada and for what reasons?

Rob: Wildlife are kept for a variety of reasons, but there’s a few that that I encounter most frequently. There are other uses of wild animals that I don’t encounter that frequently.

Bait industry

Rob: One example being the bait industry. You know, there is a huge number of animals that are wild species that are used in the bait industry for fishing.

Research

Rob: There are wild animals that are in some laboratories and wild animals that are in a variety of activities, or businesses, or industries.

Entertainment

Rob: But where I encounter them the most is in entertainment.

By entertainment, I would include not only, traditional things that people would think of as entertainment, like circuses and novelty acts, but I would also include public display facilities as well. There’s a big chunk of wildlife that are held and used by entertainment institutions, businesses, and individuals.

Exotic pets

Rob: There are also very significant numbers keeping animals for personal amusement as exotic pets. A lot of people don’t realize that if they have a bird in their house or if they have a reptile in their house, that’s a wild animal. That’s not a domesticated animal. I would say the same for probably the vast majority of fishes as well.

If you include all the individuals that that represents, fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and invertebrates, you have huge numbers of wild animals that are here in Canada.

We have a [wildlife trade] industry here in Canada that’s risen in the last 15 years or so quite considerably due to the fact that everybody can have a laptop. You can build a website in a couple of hours and you can acquire wild animals, whether large or small in a few hours as well, sometimes for next to nothing.

Mobile zoos

Rob: And that’s the educational programs in mobile zoos. That’s a whole industry that often has arisen from a hobby or somebody keeping animals for personal amusement into a part-time business. There are some full-time professional businesses that do this as well.

We didn’t see much of that 25 years ago. It hardly existed at all. But now, in Southern Ontario alone, we know of 85.

There’s more across the country. So that’s somewhere else where that we see wild animals in captivity.

Sanctuaries & rescues

Rob: There are other types of facilities that are not public display facilities, namely sanctuaries and rescue centers. There are a number of them that keep wildlife in captivity.

Government facilities

Rob: In Canada, there are some government facilities that keep seals and other animals, small numbers of them for various reasons.

Specialist exhibits

Rob: There are insect zoos in various parts of the country and a lot of these specialist types of exhibits.

When you look at what’s out there in Canada in terms of wild animals in captivity, it’s largely off the radar of most people and generally most policy makers too. But the numbers out there are not inconsequential. If you include exotic pets, there are probably millions of individuals out there that need help.

Needs of animals in captivity

Amy: When you say help, what are the biggest challenges with housing wildlife and exotic wildlife, and what are some examples of animals in Canada that are suffering right now under the current laws that we have?

Rob: The first part of your question, what are the problems with with animals? What do they face? It’s difficult to pinpoint one problem because they exist on a continuum from rather minor to very serious.

Usually when you encounter an animal, it’s facing a lot of problems. But I tried to a number of years ago, figure out a way of articulating what animals need; to get people to understand when they’re looking at an animal, what’s deficient in that animal’s life, regardless of the context in which that animal is.

It was partially spurred on by me writing kids’ books. I had to go out and talk to children for the first time in my life. That started in 2009 and I had to be able to tell them, even if they were four or five years old, what do these animals need? What are they going through?

They understood that they needed food, water, shelter. You know, the basic biological needs, the things that they were doing, eating breakfast. They could relate to those things. Even if they were four or five years old, they would get it. But I thought, Okay, what about all those other quality of life areas that are vital to the health and welfare of animals?

I came up with four, and I think they’re scientifically defensible. What I ask people to do when they think of animals in captivity is, think of these four things, understanding, of course, that they need those other things that allow them to function biologically.

Those four things are:

Space

Rob: I think that when you look at animals in captivity, wildlife in captivity but also animals in other situations, whether it’s agriculture or laboratories or whatever you see, that they are typically inhabiting spaces that are orders of magnitude smaller than the smallest home ranges that species would ever experience in the wild.

So sometimes that can be hundreds, thousands, millions, or tens of millions of times smaller than what that animal would experience in the wild.

I’ll give you an example. If you look at polar bears, which are the widest ranging terrestrial carnivore on the planet, they can inhabit territories ranging up to about 599,000 square kilometres. Pretty much equivalent to the entire province of Manitoba. If they’re pack ice bears and the pack ice floats around, that’s basically the space the more nomadic individuals inhabit at the lower end of the scale.

The Beaufort Sea Coastal Bears, some of them have home ranges measuring about 2,000-2,400 square kilometres.

The biggest polar bear exhibit in the world is more than 4 million times smaller than the smallest known home for polar bears in the wild.

If you look right across the continuum of species, from mammals to birds, to reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates, all of them, you see that typically that animals are experiencing this massive, massive compression from what they should be in, into something that by comparison is microscopically small.

I think that space is an underrated aspect of captivity. A lot of people will say, “Well, if the space is is high quality or if you enrich the environment or this or that, then you can mitigate the lack of space.” But I say, No, you can’t, because once you reach a certain threshold, it doesn’t matter.

It’s like if you put somebody in an eight foot by 10 foot cell in a prison for the rest of their life. You can pretty up that cell as much as you want. You can put pictures on the walls, you can give them a tv, a new book every day, you can do lots of things. It’s going to make a difference, but at some point it doesn’t make a meaningful difference because the space is just too small.

That, I think, is the case for animals, that you reach a threshold beyond which enrichment and other things that you can do to try to alleviate what that animal is going through don’t make a meaningful difference.

Space, or lack of space, also creates social conflict in many animals. It leads to health issues in many animals. It leads to a whole variety of things that are detrimental to the health and welfare, both physical and psychological, of that animal. So I think space is something that should always be looked at. So many other problems stem from lack of space.

There’s three questions that you ask when you look at space.

- Number one, is there enough space for the animal to express normal movements and behaviors? So normal species-typical movements and behaviors. I guarantee you go into any zoo in Canada or pretty much any zoo in Canada, and you’re going to find examples where, no, they can’t do that.

- The second question you ask is, is there enough space for animals to feel safe and secure? And there are a variety of stressors on animals; that can be visitors watching them; it can be noise; it can be construction; it can be other animals within the enclosure. You can go in zoos and other situations across Canada where animals don’t have enough space to feel safe and secure. They’re either moving away, sticking their heads in corners away from the visitor viewing stations, or they’re acting out aggressively because they feel stressed. And there’s other manifestations of it depending on the species.

- The third question you ask is, what are the consequences of not providing enough space? And we see that manifested through the roof. You know, we see pacing behaviors and other stereotypical behaviors, and many people recognize them, but they may not see, you know, looping and other kinds of locomotory stereotypies, or they may not recognize oral stereotypies. There’s the whole suite of these kinds of aberrant behaviors that manifest in captivity, and they’re linked obviously to space and lack of complexity.

But there are all kinds of other things that animals experience that are detrimental. It can be obesity, it can be loss of fitness. Over generations, it can be loss of culture. There are so many detrimental consequences to animals when they don’t have enough space. And if you know what to look for, you can walk in anywhere and see what those consequences are.

Freedom

Rob: The second one is freedom. I don’t mean we kick them all out into the wild and say, “Here you go, you’ve been in captivity your whole life, off you go. Have fun.”

What I mean is freedom of choice. And this is something that’s articulated and certainly in the academic literature, in the zoo world, that animals have to be given freedom of choice. We are included in there. It’s the way that we make a meaningful contribution to the quality of our own lives.

You know, we take away choice for people in prison. It’s a punishment. Or we give choice; often parents will do this with kids: if you’re good, we’re going to let you choose what to do.

Choice is very important. And when you look at animals, they’re just like us. They wake up in the morning and they make micro choices. Do I walk around that rock? Do I go up that hill? Do I go this way? They make thousands of these micro choices every day

And they make mid-level choices and they make very serious major choices. Like an elephant matriarch during a drought that is leading her family to water because she has that historical memory of the terrain and where water is seasonally. She’s deciding, Okay, I’m going to take my family this way because that’s giving us the best chance of survival.

These choices are how animals enhance the quality of their lives. So when they’re in captivity, you need to give them choice.

A lot of people talk about, well, we give them choice through enrichment. We give them puzzle feeders or this or that or the other thing. That’s all great. But I think that they look at providing choice through enrichment in the wrong way because the way I look at it is that if you need to artificially enrich an animal’s environment, then that automatically means that animal’s environment is deficient.

This ability to make choices is critically important to animals. And you can walk into zoos, you can walk into all kinds of other situations in Canada and see thousands, hundreds of thousands of animals that have very restricted abilities or opportunities to make choices, or in some cases, none at all.

Social context

Rob: The third is social context.

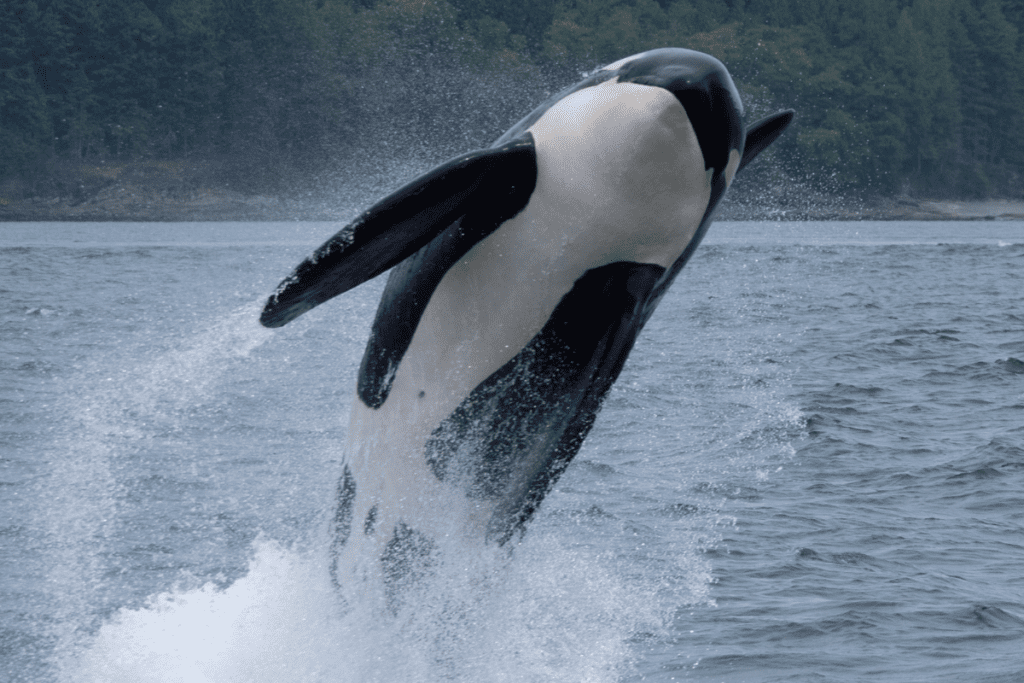

There’s a lot of animals that are not in the proper social context. You get animals that are alone when they should be with a partner, or a family, or a herd, or a troupe, or a pod, but they’re alone. That’s an insidious form of torture, especially if you’ve got animals that are hyper social like primates or parrots or other animals where they basically spend their entire lives in contact with others of their own kind.

Proper social context is important, and it’s just as important for animals that like to be alone, not to be in groups. It does work the other way. We’ve seen animals where there’s a lot of inter individual aggression.

Like Marineland here in Ontario has a bear exhibit that is about a half an acre in size. In the old days, three decades ago, they had more than 60 bears in this one exhibit. I think they’ve got 15 now, but that was an example where you’ve got way too many animals in there.

Ideally, you might have five bears in there. I’m being very generous, I would say not even one because it’s not big enough.

Activity/stimulation

Rob: And finally, and I’ve alluded to it in terms of my comments about complexity of environment.

When I’m talking to young kids, I’ll get a kid up out of the audience to stand up. I say, “What do you do in the morning?” He goes, “Well, I get up and my clothes are there and I get dressed.” And I say, “And so for the rest of the day, you just sort of stand by the bed and wait until it’s time to go to bed. Is that what you do?” And they go, “No, no. I go and get breakfast, and I check my computer to see if my friends have contacted me and I watch tv. And then I walked to school.”

I’m illustrating the fact that even though these are young kids that are not able to go out in the world and do everything that they want to do, they are doing things. They wake up, they do things from the time they get out bed until the time they go to bed.

And when I compare that to animals, animals do that too. Even ones that are often considered sedentary animals, like some of the tortoises, they’re actually super active animals. Kids get it.

So that fourth thing that all animals need is activity and stimulation.

So the kids, I have them shout out at the end, Okay, what are the four things that I’ll need? Number one, space. Number two, freedom. Number three, family (I use that with kids as the social context). And then the last one is things to do.

Animals’ needs are not being met in Canada

Rob: So I think that when people go out and look at animals, whether it’s in the circus, the zoo, the pet store, in people’s homes, and pretty much everywhere else, think of those four things, space, freedom, social context, and stimulation and activity. And I think that if people are honest with themselves, most times they’ll find deficiencies.

And sometimes it’s horrendous. Just to give an idea, some of the more extreme things I’ve seen, I’ve seen animals that have frozen to death in zoos in the winter time. They’re frozen solid, lying in a shelter box.

I’ve seen animals fed restaurant waste and that’s it.

I’ve seen animals that have never been given potable water. It’s just filthy, disgusting water that they’re given.

I’ve seen animals that are in small cages that are furnished, but the furnishings haven’t been changed in decades. So they’re biologically and behaviorally useless for those animals. They have no relevance whatsoever.

I’ve seen animals that have been mishandled by people.

I’ve seen animals that have been mutilated, so they’ve been defanged or declawed or had other procedures done that are not in their best interest.

It goes on and on and on. What I often tell people is, “Think about the worst thing that you could think that could happen to an animal in Canada, in a zoo or in some other kind of context. I guarantee that what’s out there is a thousand times worse.”

I don’t want to paint totally apocalyptic vision of what’s out there. It’s not good. But there are rays of light out there too, and people that are doing good things. Even some people in the zoo community have good motivations and are trying to mitigate current concerns and improve things. And some of them would really like to see aspects of all of these industries move in a different direction.

Alternatives for animals in captivity

Chantelle: That was such a helpful discussion of all the things animals need. You mentioned some good examples as well. I want to circle back to that for a minute because we know there are unreleasable, orphaned and injured native wildlife.

Hopefully we’ll one day transition into a new phase where we’re not bringing new animals into permanent captivity for entertainment. But there will still be captive wildlife who are already in captivity.

What would that model look like in an ideal world? Is there a good and safe way to house those animals?

Rob: If there were to be a shift in the zoo industry, for instance, that meant that their live collection plans were changing, and believe it or not, some are, but if there were this sort of wholesale change in collection planning and they decided they had to move certain animals out, the reality is that there’s too many of them.

When most people talk about good homes, they typically think of sanctuaries. Those homes don’t exist for most species. And when you look at numbers that are out there, there’s not enough spaces. So what we’re faced with is a situation where if there is a massive change in the zoo industry or even in the mobiles industry or or other areas, we’re faced with all of these animals that have nowhere to go.

So how do we deal? I think that there’s a number of things we have to do.

Address current problems

Rob: We have to work with some people in those industries to get people on board with mitigating some of the more serious problems faced by animals that are currently kept. Many of them agree are problems.

Move to suitable homes where possible

Rob: You also do want to see if there are alternative options for at least some of those animals. Maybe it’s 2%, 5%, 10%, maybe it’s more. But there are opportunities for some animals to go elsewhere.

There are some animals that could be placed in sanctuaries.

There are some animals that could be placed in a different kind of zoo, a regional zoo that is focused on that particular species. There are specialist centres throughout North America. There are quite a number of large enclosure wolf and bear centres that conceivably could take some animals.

There are private individuals who maintain animals, not as pets, but for other purposes, usually conservation that keeps them at a standard that far exceeds most zoos.

There are new facilities opening up. In fact, I spoke about the newest whale sanctuary this morning. It was the Sea Life Trust Beluga Whale Sanctuary in Iceland. There are people out there that are looking at these types of things for all kinds of animals.

There are opportunities we offer to move big cats. When zoos closed down, we did that last year. There was 15 lions and tigers. We said, “We understand that, you may have challenges in finding placement opportunities for these animals.” So we said we’ll move them because we have contacts in US sanctuaries. We’ve done that with other animals as well.

Repatriation

Rob: Another option that I think is worth exploring is repatriation of animals to the wild. And I know that in the past zoo people used to really sort of jump on that saying it’s ridiculous. But when you think about it, are not the release programs that zoos either promulgate or support doing the same thing? They’re taking animals from captivity and trying to release them into the wild for conservation purposes. There’s nothing that says you can’t do that for welfare purposes, and there has been a long history of it.

This morning when I was talking about whales and dolphins, I mentioned the Into the Blue project, which was more than two decades ago, and other releases that seemed to work out quite well. There have been long term captive elephants released successfully back to the wild. There have benn lions and tigers that have never had the pads of their feet touch grass that have been released.

There are huge challenges in doing it, and it’s not an option for every animal, but I think that repatriation, if not to truly wild settings, to sort of game reserve type settings might be an option for animals.

I have a children’s book called Five Elephants, and I talk about this elephant called Thandora that lived for 18 years in the South African. The other elephant she was with died. The zoo decided they had to do the right thing and they repatriated Thandora to a 18,000 acre reserve. It wasn’t the true wild; Thandora couldn’t migrate. But it was a vast amount of space with all of the other indigenous wildlife and opportunities for Thandora to do what she wanted.

So I think there are probably a lot more of those kinds of opportunities for animals than most people think.

Euthanasia

Rob: The fourth option is euthanasia. I know people don’t like to hear that, but that is a reality. If there are no other options, if you can’t improve and enhance the conditions of that animal in the zoo or wherever it is, or if you can’t repatriate it, or if all those options have been exhausted, then the right thing to do as euthanasia because, at least in my view, I find it inconceivable that anyone could walk away and leave an animal in some of the circumstances I’ve seen where it’s fighting every day against the cold to survive, to get enough calories to maintain its body weight, that it’s in a situation of mind-numbing boredom for days or weeks or months or years, basically a living death.

I don’t think that’s an ethical thing to do to leave animals in those situations. So I think euthanasia should always be sort of in the back there as well, when all other options have been exhausted.

But I think there are things that can be done.

Just to sort of bring it back the first one though, because these other options, placement opportunities, repatriation, it may involve good numbers of animals. It may not.

Preventing future suffering

Rob: But the real sad fact of the matter is that we’ve got to do the best we can where animals are now: prevent their breeding, prevent their importation, make sure that we stop the problem with this group of animals and we don’t just let it continue on into the future.

That, to me as an advocate for animals, is what I try to keep in mind all the time. That we do the best we can for these animals that are here. But maybe we can’t help them or maybe we can’t help them the way that we want.

But we have to have our eyes on the goal, which is: let’s stop the process that put all these animals into that position in the first place. That is the first priority when we’re approaching these kinds of things.

Let’s stop the system. Let’s make that systemic change. Let’s not just deal with the fallout or the symptoms.

Exotic animal laws in Canada

Amy: That’s a good transition into the talking about laws. What kind of laws are in place for wildlife, whether they be imported or already in captivity, and what ideas do you have for new laws or improving existing?

Rob: Well, in Canada, we have this reputation as being a law abiding nation. I think that in some respects that’s true, but in other respects it’s not.

When it comes to animals, we’re not really big on laws for animals in Canada with regard to imports. There is sort of a loose network of laws.

Federal laws around exotic animals

Rob: You have regulations that govern the import of, for example, turtles or some primates through the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. A lot of people might be surprised with that because their primary mandate is to deal with food safety; but they issue permits for the importation of certain kinds of animals that people keep as pets and for other reasons.

So you’ve got that, you’ve got the Migratory Birds Convention Act, but what most people look at when they look federally at laws regarding animals and the import of particularly wild animals is the Convention on International Trade and Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), a convention that Canada is a signatory to.

So in order to deliver Canadian obligations under cites, they have a federal act called the Wild Animal and Plant Protection and Regulation of International and Interprovincial Trade Act. It delivers on our CITES obligations and controls the import of CITES listed species.

Now, CITES listed species are those species that are endangered or could be endangered by trade. So if it’s pollution or something else, CITES may not kick in. You’ve got a limited number of species that are covered by CITES, so that has some implications for the importation of certain animals. Although, as with most treaties and and laws, there are exemptions.

Provincial laws around exotic animals

Rob: But most of the responsibility for dealing with captive wildlife has been delegated to the provinces.

In Ontario, we have our Provincial Animal Welfare Services Act, and those inspectors will look at zoos and they’re supposed to be working on regulations for zoos because it is a provincial responsibility.

In British Columbia, you have the Controlled Alien Species Regulation under the Wildlife Act because kept the wildlife is a provincial jurisdiction.

So what we have in Canada is this mishmash of laws, some commonalities, a lot of inconsistencies from province to province and in the territories.

Municipal laws around exotic animals

Rob: There is then also a lower level being the municipal level, or sometimes regional governments deal with this too.

When you look at those bylaws, there are some commonalities right across the country, but there’s tremendous inconsistencies because the people who are writing them generally don’t have the necessary expertise to actually write them. And I don’t mean in terms of the legalese and laying out procedures for enforcement. I’m talking about the animals themselves and the needs of the animals. What should they require? If they go into standards for housing and things like that, they don’t have the expertise.

I know so many animal control officials that actually work on these issues, and they look at the prohibited lists or positive lists of animals, and I’ve had many of them say to me, I have no idea what all these mean. You’ve got all these municipalities and all these people who lack the necessary training to develop the laws that affect these animals.

Criminal Code of Canada

Rob: The only other things that I haven’t mentioned are the Criminal Code of Canada, but that’s not really, in most cases, a useful tool for trying to deal with animal cruelty. It’s not set up as something to be beneficial to animals. The criminal code is identifying behavior that is inappropriate to society.

Most people feel that some behaviors like dragging your dog behind your car until your dog’s dead are just not acceptable. That’s more what the Criminal Code would deal with, rather than with any kind of institutional or commercial mass cruelties, whether it’s zoos or the meat industry.

It’s really challenging when there is this mishmash of laws to try to do something. We’ve had enormous challenges over the years in trying to get these laws noticed, get them interpreted in a reasonable scientific way, and then getting them enforced.

We always say that half the battle is getting a law in place and the next half of the battle is getting it enforced. That really been the case here in Canada. But it’s a mess.

In India when you look at wildlife and captivity and public display facilities, they have the Central Zoo Authority. Public display facilities and zoos comes through them. In the UK you have the Zoo Licensing Act, and in other jurisdictions you have other things that just say, Okay, this is the agency that deals with this issue and these are the standards and these are the rules.

We don’t have anything like that in Canada.

That’s why we have people who have big cats in Alberta that are not supposed to be there, and then they’re found out, they drive over to Ontario, they end up in a municipality where there’s a bylaw against that. So they move to the next municipality and then the next, and you know, we have all this inter provincial movement and within provinces as well, because our laws are such a mess.

That’s why I’m hopeful about the Jane Goodall Act because that I think would move the needle in the right direction quite.

Chantelle: It’s become a theme with our podcast is that it’s such a patchwork whenever there’s animal laws in Canada, whether it’s provincial or federal or municipal.

Who is left out in exotic animal laws?

Rob: I should mention one other thing that’s an important point. Most of our laws don’t help all the animals. So if you look at municipal bylaws, many of them have a prohibited list.

Your local municipal bylaw might say can’t have that tiger. So you might be in trouble if you have it. Or if you haven’t got it, you’re thinking of getting it, then it may make you think, I’m not going to get this because this is going to be a big problem. My municipality doesn’t allow it.

But when you look at municipal bylaws across the country, and when you look at many provincial laws as well, you notice something very peculiar.

And that is that they are mammal centric; that there are very few birds, very few reptiles, typically no amphibians, and typically no invertebrates listed yet. When you look at the numbers of species, there’s about 6,000 species of mammals, but there’s more than 10,000 species of birds, 12,000 species of reptiles, 8,000 species of amphibians, 30,000 documented species of fish, and who knows how many invertebrates.

Most of the animals that exist today, many that could end up in a commercial operation in someone’s home as a pet, in a circus or in a zoo. They don’t even show up in these laws. That is a massive deficit.

Most people think that if you have an anti cruelty law or if you have a law controlling exotic animals, it’s all good, but it only deals with a very small number of animals, a very small number of species. It does not represent the diversity that exists out there in the world, or that exists in the industries and people that exploit these animals.

There are over 7,000 species documented in live wildlife trade, much of it for the pet trade. That’s a huge number. Most of those are not represented in any laws.

It’s a very challenging situation here in Canada.

I’ll just finish that answer by saying with regard to zoos, every province in Canada has something. It’s either a policy or something in regulation or a law that addresses some aspect of it. A lot of them are not very good, but it’s something.

In Ontario, we have nothing. Anybody can go out and buy spitting cobras and black mambas and tigers and zebras and aardvarks and whatever else. You want to think up and open a zoo, and there’s no license required. You don’t need any expertise. You don’t need any mentoring. You don’t need any professional affiliations. You don’t need any relevant experience.

There’s no mandated standards for caging for any kind of animal, and there’s no convenient way for the province or anybody else to close the zoo. So the worst in the country is here in Ontario in terms of controls or regulation of this sector of animals.

What you can do to help animals in captivity

Chantelle: Before we wrap up, what would you suggest that our listeners can do to advocate for wildlife in captivity?

Rob: Well, number one, get political. We have a very tiny number of people in this country that are getting political for animals.

The reality is the big changes that we all want to see happen will come politically. We can work on a lot of things and make things happen, but those big societal changes that we want to see have to come through politics.

And I would say to people that if you’ve got an interest in trying to help any issue, it could be animals, it could be poverty relief, it could be affordable housing, the environment. You’ve got an issue that you’re concerned about.

Understand how the systems that govern your life work. Anybody can learn how the system works, and that to me is the first step in understanding what you can do about it.

And everybody has different capacity. Some people may be able to drop everything in their life andbe a full-time activist doing this 24 hours a day. Other people, maybe not so much. Maybe they’re restricted to one hour a week.

But I think the first step once you’ve identified an issue is understanding the system and how what you want done could actually happen within the context of that system.

I can tell you absolutely 100% certainty people can actually change things. And I use ourselves as an example. A lot of the things that that we’ve tackled over the years we’ve started at from the ground up against opposition with very deep pockets and we win.

We have a pro-democracy advocate here in Ontario. He would say, “If you don’t know the rules of the game, you can’t play.”

This is something that we’re moving into. We’re going to be putting together very soon, uh, an advocacy program so that people have more information about how they learn, what they should learn, and how they can affect change.

Because honestly, people can do it. You can really do it.

Next episode

Watch out for the next episode of The Informed Animal Ally on November 28 about animals used in research.