Wild animals think, feel, play, grow together, have families, and help maintain a healthy and harmonious environment; yet many human activities put wildlife at unnecessary risk of suffering.

In this month’s episode of The Informed Animal Ally’s series on animal cruelty, Wild Animal Welfare Specialist Erin Ryan from the BC SPCA joins the Vancouver Humane Society’s Amy Morris and Chantelle Archambault to discuss wildlife stewardship, feeding, poisons, and more.

Note: This written interview has been edited for length.

Featured Guest: Erin Ryan

Wild Animal Welfare Specialist

Erin is a member of the Syilx nation and holds a BSc in applied biology and an MSc in Applied Animal Biology from the University of British Columbia. She works as a Wild Animal Welfare Specialist with the BC SPCA’s Science and Policy division, focusing on wildlife welfare, including urban wildlife and rodent control.

- Wildlife and Indigenous ways of knowing

- Wildlife protection laws in Canada, British Columbia, and municipalities

- Laws around spirit bears in B.C.

- Laws around wolves in B.C.

- Laws around pigeons in B.C.

- Limits on animal welfare legislation

- How do rodenticides harm wildlife?

- Rodent poison laws in British Columbia

- Calling for change in local elections

- Laws around captive wild animals

- Next episode

Wildlife and Indigenous ways of knowing

Amy: Could you share a little bit of your background working with wildlife and what drew you to this work?

Erin: I think a big influence to the work that I’m doing now is my grandfather [who was a biologist and the first indigenous MP]. Even though many people remember him as a politician, he really thought of himself as a scientist.

I remember growing up, in the forested gully of their backyard, learning all about the plants and animals that grew all around us. And of course, a lot of our approaches to how we handled wildlife encounters in that backyard are kind of what I’m advocating for people to do today.

Amy: Your family has had a really interesting history of bringing an Indigenous perspective into federal decision making. Can you share some of your learnings on the relationship between wildlife and Indigenous communities as it relates to Indigenous laws and ways of knowing?

Erin: I think the main difference that I’ve seen, looking at my world of wild animal welfare, is so many of our laws and systems are built into this perspective of wildlife management; that is our job to manage the populations and to manage the environment. Whereas the values that were instilled in me from a young age and a lot of traditional Indigenous values are more about stewardship.

If we’re good stewards of the land, good stewards of the animals, we are taking care of them, but they’re also taking care of us. There’s much more this sense of reciprocity and that we’re sharing this system together. We don’t have dominion over the animals and need to control the environment.

Amy: Yeah. That’s certainly something that I think there’s a lot of space for moving towards and having more of in the world that we live in.

I’m curious. I know there’s been some consultation from the B.C. provincial government that resulted in a bill, Bill 14. And a big part of that brings into legislation, more collaboration and acknowledgement of Indigenous communities’ role in maintaining our wild populations. So I’m curious to hear if you have any thoughts on that.

Erin: So what this bill is essentially doing is the short term amendments to the Wildlife Act. Of course, the Wildlife Act is maybe one of those canonical pieces of legislation that were originally built on a very Western perspective about how we need to manage and control animals and legislate and enforce.

At the time the Wildlife Act was initially built, our government wasn’t thinking anything towards reconciliation or towards incorporating Indigenous perspectives. And I think seeing these changes really reflects that changing relationship and seeing more of government to government work. What it kind of allows for is it gives Indigenous title and right more sovereignty, the right to govern themselves as they always have since time immemorial.

It also incorporates systems for incorporating Indigenous ways of knowing, and not just relying on traditional Western science to dictate how we approach wildlife management in the province.

Amy: I think everything that I’ve heard and learned about sustainability of wildlife is that the focus needs to be on observing, of paying attention and taking time and not making sudden decisions that could affect a whole ecosystem based on, you know, one test or one experiment. So from your perspective, how does Indigenous wildlife stewardship compare with colonial laws?

Erin: Again, I think it’s much more that perspective of stewardship versus management. So there is a lot of this inherent traditional knowledge that goes to our approaches with wildlife.

And I think even before there was a word within Western science for the One Health, One Welfare approach, that was largely how Indigenous people lived. It was knowing that the way the health of the land was interconnected to the health of the animals and to the health of the people and that we all share the system.

If one of us suffers, we all suffer. But if we take good care of each other, then we all can thrive.

Wildlife protection laws in Canada, British Columbia, and municipalities

Chantelle: Backing up a little bit, we’ve been talking about colonial laws and you mentioned the Wildlife Act. When it comes to colonial laws, we have the three levels of legislation to consider: federal, provincial, and municipal. Could you give a little bit of background for our listeners on what protections are in place for wildlife at those three levels?

Erin: For sure. So at the federal level, this largely looks at species that are particularly endangered or considered at risk or perhaps part of threatened habitats. It also provides protection to animals in protected areas like national parks or national nature reserves and things like that. One of the primary pieces of federal legislation that I deal with is the federal Migratory Birds Convention Act. Because it tends to be that all these migratory birds are not just present, as we know, in one locality or one province; they tend to move throughout the landscape.

At the provincial level, we see the B.C. Wildlife Act, and that helps to fill in some of the gaps of how wildlife is managed at a provincial level. So this piece of legislation and at the provincial level is where we see things like hunting and trapping regulations; we see species limits, bag limits; it defines allowable hunting regions. It also prescribes a few more pieces of legislation for things like wildlife feeding. So the B.C. Wildlife Act prohibits the feeding of dangerous wildlife like bears and wolves and cougars, but it does leave a big gap for other animals.

And this is where municipal law can come in. So although some of those bigger, broader changes aren’t necessarily jurisdiction of the municipality, it is still really important that municipal bylaws can fill in, even more, some of those gaps.

So if we take a look at wildlife feeding, municipalities have the power to say it’s a ticketable offense to feed wildlife, and that can include all types of animals, whether it’s raccoons or squirrels or geese in parks, in ways that are unhealthy and harmful. And unfortunately, even though it might feel good or catch a nice photo, we know that wildlife feeding rarely results in a good outcome and the people who suffer are the animals.

Laws around spirit bears in B.C.

Amy: I was wondering, for me as a person reviewing legislation, it can be really overwhelming sometimes to think about the thousands, maybe tens of thousands of species that there are, and the way that the law tries to make different categories and rules around not just individual species, but geographic areas. And I thought if we could take a couple individual species of animals and maybe chat through. How it looks; what laws apply; and what some outcomes are for individual animals.

One that comes to mind for many people is the spirit bear, or the white variation of the black bear, and how laws have been developed to protect that bear. I’m curious what you know about that.

Erin: I have heard that there have been some changes incorporating Indigenous laws. So I know that although the province sets black bear hunting levels across different regions and different seasons, there are some Indigenous nations that have their own laws about which types of traps are appropriate, what their hunting season is. And I think what we’re seeing is those are starting to align. And there have been pushes, for example, in changes to black bear hunting limits in order to try and protect spirit bears, because we know that this is a genetic minority and something that has incredible cultural and spiritual significance to a lot of people.

Amy: And I guess some areas just no hunting can occur at all for black bears. Is that right?

Erin: Indeed. In some areas.

Laws around wolves in B.C.

Amy: That’s kind of a happy story, right? Seeing change and seeing more protection.

I’m wondering if we could talk a little bit about wolves, certainly not as happy of a story.

Many people know, but just in case there are some who don’t: in B.C., there is a wolf cull that has ongoing has been ongoing since 2015, where quite a large volume of wolves are being culled. Essentially killed by helicopter and other means by the province and it’s being paid for with tax dollars. And I’m curious about if you have any knowledge around how the law has come to be, that that’s allowed. What makes it okay to kill these animals in large numbers?

Erin: I think the biggest piece is that it’s become a directive from the provincial government. So whatever restrictions have been in place can potentially change. I know there was a case taken forward. Pacific Wild actually tried to bring forward a legal case that the killing methods of shooting these wolves aerially from helicopters was against the B.C. Wildlife Act.

It is challenging because it highlights some of the really horrible methods that are actually legal. So at this point in time, the use of baiting and poisons and aerial shooting are all completely within the bounds of the law.

I think we can look at this project and definitely disagree. The science all points toward habitat disturbance being the primary factor to caribou decline, which then allows wolves to access the landscape. But in that same sense of wildlife management versus wildlife stewardship, if we’re trying to manage, we’re not going to be able to shoot our way out of this problem.

We have recent evidence showing that habitat restoration of these disturbed areas can restore the landscape and can protect caribou. And if you look at what your tax dollars are paying for, really I would prefer to see my tax dollars invested in habitat restoration.

Amy: It seems to me like that would be the case of most people.

Erin: Indeed. There’s a high percentage of British Colombians, and my mentor, Dr. Dubois did some research on this area, that 95% of British Columbians didn’t agree with killing one species to save another, even if they were endangered.

Laws around pigeons in B.C.

Amy: Wow. So maybe moving on to another species.

There are a number of animals that we share our environment with that were brought to where we live. Pigeons are one that we now consider wild because they don’t want to be handled. They don’t necessarily want to be close to us anymore, but they’re all around us, especially in city environments.

And so what are the rules around pigeons and animals like that who aren’t necessarily from our area originally? Are there laws about them?

Erin: I’m so glad you chose pigeons, because I love to talk about pigeons. They’re a particularly interesting case species. So there’s such a divide in our legislation about the way we treat these animals versus the exact context and circumstances of how they came to the environment, how they exist in the environment, their effects.

But pigeons are listed in what’s called Schedule C of the B.C. Wildlife Act. And some other animals included in there, up until recently, included crows, which are native species, brown headed cowbirds, also a native species. These two have recently been moved to Schedule B. But it also includes things like bullfrogs and nutria and feral pigs and all kinds of different animals. And you can see that none of these have quite the same story as the others.

Pigeons, for example, have followed humans to so many corners of the earth. Pigeons in North America arrived really with the first settlers and have become so integrated into the environment that even if we tried, I don’t think we could ever realistically remove pigeons from the landscape. And they’ve been here for hundreds of years.

So it seems hardly fair to be treating them the same way when they’re not having that demonstrable negative impact on the environment. Versus if we look at another Schedule C species like bullfrogs, they are surprisingly voracious predators. They will eat anything that fits into their mouth, even things like ducklings. So there is still hope that we can remove the bullfrog from the landscape. And we know that they have a negative impact on the environment. They were introduced to B.C. much more recently. And yet the same legislation applies to pigeons as it does to bullfrogs.

Amy: And so does Schedule C mean that pigeons aren’t offered the same protections as other wildlife?

Erin: Exactly. So under the Schedule C species, these animals can be killed at any time of year in any number with no limits.

Limits on animal welfare legislation

Amy: Are there limits to the welfare of that process? You know, what laws come into play when you talk about what’s humane?

Erin: The tricky part is that for so long, our legislation has been focused on cruelty and prevention of cruelty.

A lot of the protections that are in place are the bare minimum protection from cruelty. So at the federal level, animals are protected under the Criminal Code, which doesn’t allow animals to be willfully in distress. “Willful” is hard to prove, but this would be, you know, in the worst circumstances where we’ve seen people, for example, maliciously harming an animal.

Animals are also protected under the provincial Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act. So this is the Act in which the BC SPCA has its enforcement powers to enforce cruelty legislation and bring those to Crown Council. Another tricky part with this one is that these acts generally exclude what’s considered “industry best practices”.

So for example, we know that with farm animals, a lot of circumstances that we see are not considered high welfare, but they are considered industry best practices. And for that reason, a lot of cruelty legislation wouldn’t apply.

How do rodenticides harm wildlife?

Amy: I think that’s a really good transition actually into our next area. Because when we talk about provincial legislation and municipal bylaws, one topic that has recently been making headlines is the topic of rodenticides, or rodent poisons, because of the danger they pose to wild animals and pets.

There have recently been some changes to legislation around rodenticides, which we’ll get into later. But first, could you touch on why these poisons are so controversial and a hazard to wildlife?

Erin: Yeah. So a lot of the legislation and sort of the big momentum changes happening right now is regulating the use of what’s called second generation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs).

An anticoagulant is a poison which thins the blood. So it leads to bleeding and hemorrhaging. And usually death happens when the animals simply bleed out. So in sort of the early 1940s, 1950s, we developed what’s called first generation anticoagulants.

Over time, animals developed resistance to these products and there was sort of a lower toxicity. So it could take a few times of them ingesting this product before it would have its effect. For example, warfarin, we see a lot of resistance to this product. And for that reason, we looked towards developing second generation anticoagulants.

So these products were designed to be much more toxic so that rodents could be poisoned after just a single feeding. However, that also meant they’re much more toxic in the environment and they persist much more in the environment.

Animals experience what’s called direct poisoning or secondary poisoning.

Direct poisoning is what we see happening to the mice and rats. So they’re actually eating the poison and they’re experiencing the effects of the poison.

Secondary poisoning is when an animal like an owl, an eagle, a hawk, eats a poisoned rodent carcass. And when they eat enough of that, they themselves experience this sort of secondary toxicity as it builds up in their system. And unfortunately, they experience the same suffering and the same effects.

We’ve noticed pretty profound levels of poisoning. And that concern for wildlife is largely what has driven legislative changes right now. There are also non anticoagulant rodenticides, and these are poisons that work in all kinds of different ways. So for example, there is a neurotoxin bromethalin, which causes effects of the central nervous system. It causes respiratory distress and it’s also one of those rodenticides that has no antidote.

Rodent poison laws in British Columbia

Chantelle: That was a really helpful background on what rodenticides are. Thank you. There’s been some changes around the laws, as you mentioned. And now there’s a partial ban on the second generation anticoagulant rodenticides. Could you give some details on what that partial ban entails?

Erin: So, as you mentioned, the ban is just a temporary order that affects only the second generation. So that means the first generation anticoagulants are still legal for use. And it means that the non anticoagulant rodenticides are also still legal for use, including these neurotoxins.

And the reason they targeted SGARs is to really tackle the angle of wildlife poisoning and to try and prevent that. So there’s a temporary Minister’s order in place. Although there are still some exemptions for essential services. And the hope is that there will be updates to the legislation when the order expires next year.

And I am hopeful for what’s coming out of the legislation. It’s really inspiring to see the Minister’s ordered last year. It’s not something I expected to see for a long, long time.

Amy: Yeah. It seems as if there’s some real awareness of the public value that other animals have. Maybe rats don’t have public value to the government and many entities, although they have value to us.

But that value in owls and other species, that there’s enough value that the government is recognizing that they’re willing to put financial resources into even developing policy. In so many cases, even if people care about something, the government doesn’t put resources into looking into it, just because they don’t have maybe the same severity of seeing the public perception as being important.

And in this case, it seems they’ve gone forward and said, yes, we do care about public perception and public experience. There are still some gaps in the legislation, but also continued reports from wildlife rescues and veterinarians where poisons are still being used and animals are still suffering.

Do any cases come to mind of confirmed or suspected rodenticide poisoning in wildlife?

Erin: I think one of the things that’s important to remember is that these poisonings often go undetected. So, for example, with wildlife rehabilitation centers, these are often not-for-profit charitable organizations that don’t have a lot of money to invest in poison testing. And this does take money and it takes time.

It can often go undetected because if an owl, for example, is experiencing secondary poisoning, even if the poison doesn’t kill them, or isn’t the obvious cause of death, it does make them more likely to be involved with things like vehicle collisions. And so when they present, it may appear that this owl was hit by a car and that’s the cause of death, not realizing that maybe what we should be looking for is also a rodenticide test.

It’s hard to know what we don’t know. And there have been a number of scientific studies showing a shockingly high percentage of carcasses that tested positive for residue. Whether or not that was the cause of death, it’s still in their system.

And certainly, the members of the public who have found poisoned wildlife have been huge in making this effort. You know, there was one report from the same area where they found more than four owls that had died by rodenticide poisoning. And those cases really speak to the public.

They know what they’re seeing is wrong and they want to take action.

Chantelle: That’s a really good point about the difficulty tracking how many animals are being poisoned by rodenticides if we’re not testing them. Because we know policy change is more attainable when it’s backed by accurate and consistent data. So that’s probably why these reports haven’t yet resulted in a comprehensive ban on all rodenticides.

And the four owls that you mentioned that were found in the same area, which were found in North Saanich, were found around an area that has several farms, where second generation anticoagulants are still allowed.

Calling for change in local elections

Chantelle: We have the municipal elections coming up and that’s a great opportunity to advocate for more animal-friendly bylaw commitments. Would you be able to talk a little bit about what authority municipal governments have to limit the use of rodenticides or make other laws to protect wild animals like with fireworks?

Erin: So, as we discussed earlier, municipalities really have that ability to fill in gaps that are left behind by either provincial or federal legislation. For rodenticides, we’ve actually seen that municipalities have made a huge difference in motive for the province to come down with that legislation.

So I think it’s nearly 30 municipalities now have banned all rodenticides or restricted rodenticides on their municipal property. So even though they can’t ban rodenticide use completely in the city, they can say what is allowed on their property.

And that has a huge impact, because this isn’t just one building. It includes all of their operational offices. It might include community centers, sports centers, and all kinds of different venues. So it covers quite a bit of ground. And it also brings the issue of awareness to the public eye. And I think for the provincial government, it showed that municipalities were willing to work on this, that they weren’t going to get pushback if they tried move forward with this legislation.

Amy: Then I guess there’s also some good bylaws that could be put in place for preventing wildlife feeding. Now is the time to ask either candidates, or if you’re listening to this later, elected folks to consider putting a bylaw in place around wildlife feeding or about banning fireworks or fireworks with sound.

And certainly outside of B.C., there is a municipal cycle that goes on as well. So any time is a good time to ask for change. As we know, it sometimes takes quite a while to get change in place when it comes to public policy, so best to get started sooner rather than later.

So we’ve spoken pretty in depth about the current legislation and gaps. What would you say still needs to be done to protect wildlife?

Erin: You brought up an excellent point with wildlife feeding. That’s definitely an issue that’s top of mind for us as we come into municipal elections. And this is just one of many ways that they can step in and fill a gap.

Where the province regulates the feeding of dangerous wildlife like bears and coyotes, it doesn’t regulate things that the municipal level can. So for example, the City of Vancouver has one of the more comprehensive bylaws we’ve seen prohibiting wildlife feeding, and that includes all species. Previously, there was a bylaw in place for Vancouver parks, but this now applies to the entire city of Vancouver.

Amy: That’s huge.

Erin: It is huge. And the BC SPCA has some examples of model bylaws that are available on our website. We’ve just updated our new model bylaw tool so that municipalities can actually go and look at examples of bylaws that we reviewed and we believe how the animal’s best interests in mind.

Amy: It certainly seems like having one municipality take action on something helps for other municipalities to follow suit. You know, have you worked on any cases where a municipality was the first to adopt something? Curious about how that happened if you have experience with that.

Erin: For sure. I think for me top of mind, when it comes to rodenticides, was the District of North Vancouver. So they weren’t necessarily the first municipality in B.C. to pass legislation about rodenticides, but they certainly were sort of the biggest and the most vocal and they certainly developed the most comprehensive policy.

So the District of North Vancouver has also helped inspire other communities. And they can say, “Well, if a big municipality like the District of North Vancouver can do it, so can we.”

Because they also have this comprehensive policy that serves as a model for other municipalities and they don’t have to start from scratch. They already have something usable and comprehensive in place.

Amy: That certainly makes it easier to advocate. Do you have any advice for people who are in advocating for better laws for wildlife?

Erin: The most effective approach to try and make change is to talk to your elected officials. Because they want to make change that matters to their constituents, and if they don’t hear from you, they don’t know that it matters to you.

So the easiest thing you can do is email your City Councillors, Mayor and Council, email your MPs and MLAs, and let them know what animal issues are important to you and what you want to see. You can also even point them to our model bylaws and say, “I’d like to see something like this” or “This nearby district has this great bylaw. Is this something we could consider adopting?”

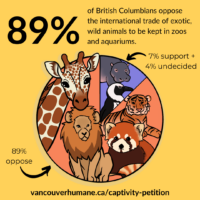

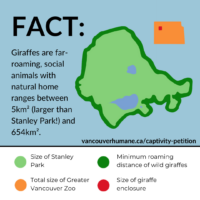

Laws around captive wild animals

Amy: As we segue into our next episode, we talked about fish welfare before, and then we’re moving on to laws around captive wild animals next month, taking a little bit of an in depth look at that aspect of wild animal welfare.

Do you have any thoughts to share on this topic? Are there ethical and non-ethical ways of keeping wildlife in captivity and is there room for improvement in the laws?

Erin: I think there’s certainly room for improvement. We talked a little bit about some of that cruelty legislation and how industry best practices or generally accepted best practices are excluded.

I think there is no denying that animals don’t have everything they need when we confine them in small spaces and put them up for public display. But unfortunately, if their nutritional needs are met and they’re not in neglect or distress, there’s not a lot legally that’s in place to protect them.

Amy: Yes, absolutely. I’m curious to see what can be done for stereotypical behavior.

Next episode

Watch out for the next episode of The Informed Animal Ally on October 25 about wild and exotic animals in captivity.