What can we do to help wildlife?

There are many ways that human activities, infrastructure, and policies impact wild animals. On this month’s episode of The Informed Animal Ally, the Vancouver Humane Society’s Amy Morris and Chantelle Archambault discuss the ways in which animal allies can speak up for wildlife.

Note: This written discussion has been edited for length.

Compassionate conservation

Chantelle: Last month we talked about farmed animals and went through their natural behaviours species by species. This month will be a little different, since we’re talking about wildlife and there are so many species.

Amy: Before we get into it, I want to touch on an important piece of background for this discussion. Conservation is a topic that comes up a lot when people talk about wild animals, but it’s often about preserving the species and maintaining biodiversity, without looking at the well-being of individual animals. The lens we’ll be using today is compassionate conservation, which includes the guiding principles:

- First, do no harm

- Individuals matter

- Inclusivity

- Peaceful coexistence between animals and humans

Throughout this episode we’ll be talking about ways you can help protect wild animals from the threats they face, and it’s important to bear in mind through all these advocacy actions that the goal is to treat wildlife with respect, justice, and compassion, and to allow them to thrive. There is a great infographic on this.

Urban wildlife

Chantelle: Absolutely, thanks so much Amy. Now that we’ve covered that, I think it makes sense to start with a brief overview of some of the ways humans interact with wild animals. When we think of most people’s day-to-day interactions with wild animals, many people living in cities, towns, or suburbs will think about urban wildlife. Urban wildlife refers to animals who have adapted to survive alongside humans and the infrastructure we’ve developed. Those adaptations can include taking advantage of new food sources, like garbage or some types of plants, or building their nests in human-made structures.

Amy: Urban wildlife may show signs of being habituated, or unafraid of, people. This happens over time as they encounter situations that feel safer and safer; alternately, they find ways to navigate in the human world that avoids people entirely. Just like with humans, wild animals will be afraid of what they don’t know, and comfortable with anything that feels familiar and safe.

Some urban wildlife are considered synanthropic species, which means they thrive in human environments. Think of adaptations like pigeons nesting in buildings and eating dropped food, squirrels living in trees from parks and gardens, rats commonly living in sewers or buildings. Some people consider these species to be “pests” because living in such close proximity can lead to human-wildlife conflict.

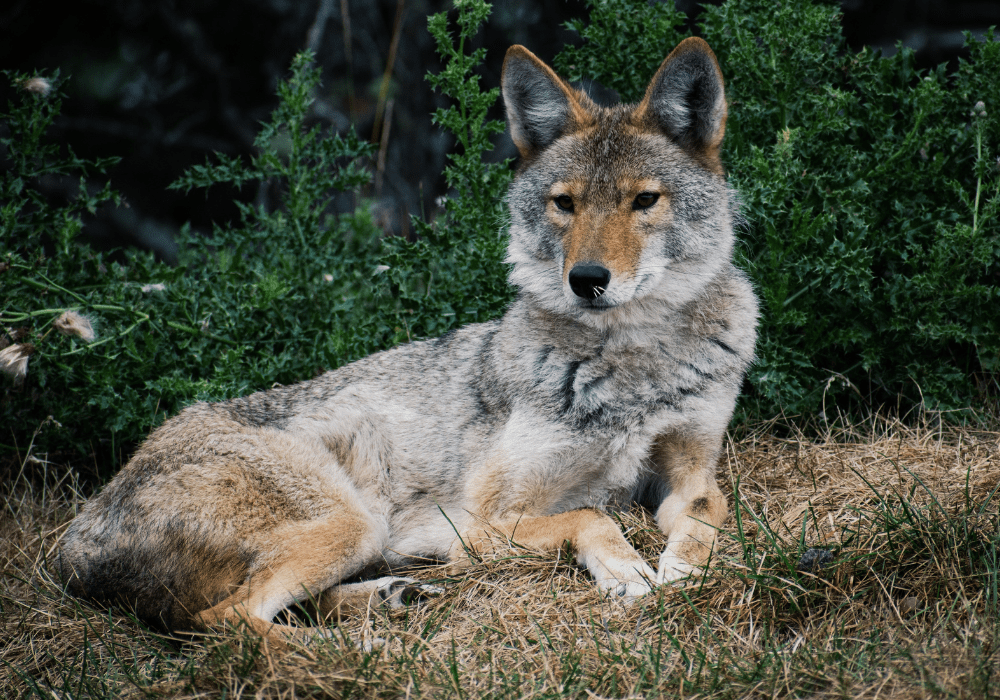

Other urban wildlife often live alongside humans in urban environments, but they aren’t as dependent on human activities to survive. If you think of an animal like coyotes, they’re generally considered an opportunistic species so they can exploit the resources in human environments like eating small animals, fruits and vegetables, or garbage; but they can also survive in a more natural landscape. They’re also typically more wary of humans.

Threats to urban wildlife

Chantelle: That brings us to talking about some of the threats urban wildlife can face. You mentioned human-wildlife conflict and that’s something that can have a very negative impact on animals. Generally, conflict arises when animals are causing damage like chewing walls, making messes like knocking over garbage bins, or if they’re posing a threat or perceived threat to human or pet safety, such as skunks nesting below a shed and the people who live in the home being afraid of their dog being sprayed. In those situations, the outcome for the animal is usually very negative or even deadly. Often animals are killed—two issues that have been really top of mind over the past year are rodent poisons and culls.

Amy: I can speak more to the poison issue. Rodenticides, or rodent poisons cause a great deal of suffering to animals. There are a few different categories of poisons which we spoke about in our wildlife episode with Erin Ryan last year, so please listen to that episode if you’d like more details.

Essentially, poisons don’t work immediately and cause animals to die slowly and painfully. Anticoagulant rodenticides work by thinning the blood so animals die by bleeding out or hemorrhaging. Those are the poisons most often used in Canada.

There are also other poisons like neurotoxins, which cause the nervous system to shut down so animals can experience symptoms painful and scary symptoms like weakness, loss of coordination, convulsions, and respiratory distress.

We’ve had some progress here in B.C. with permanent restrictions on second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs), which are some of the most dangerous poisons and also some of the most likely to cause secondary poisoning to predator or scavenger animals, like owls or eagles, who eat poisoned rodents; but there are still exceptions where those poisons can be used.

First-generation anticoagulants and other poisons are also still allowed.

Chantelle: Several municipalities have taken the compassionate step of banning all rodenticides on the city or town property. A great way to advocate for animals harmed by poisons is to ask your Council or the building manager where you live or work to commit to poison-free methods.

There are also government sanctioned culls of animals. The Vancouver Park Board recently approved a plan that includes the option of killing geese to control their populations, which is inhumane and unnecessary. Evidence shows that habitat modification is a more effective long-term method. There was also the coyote cull in Vancouver’s Stanley Park in 2021 that happened after people reported coyotes approaching and biting them. In total, 13 coyotes were killed. This could have been prevented if better methods were implemented to prevent the feeding of animals in the park and remove attractants like garbage that draw coyotes toward human areas.

How you can help urban wildlife

Amy: Prevention is the best and most effective method of dealing with conflict with wildlife. You can prevent animals like rodents from entering buildings by sealing up access points and removing or sealing away food and other attractants.

The most important thing we can do is to make sure wildlife continue to be afraid of anything that might hurt them. This is why it is so crucial to not feed wildlife. If you feed wildlife, they start to see people as a source of food. They also can become dependent on the food being provided and then if it is removed, they can become aggressive. We would do the same if we were fed regularly and then suddenly all the food was gone, with nothing available to us… I have been around some pretty “hangry” people and I imagine it can get pretty bad when an animal feels truly desperate from their hunger.

Chantelle: Absolutely. Another way people deal with wildlife conflict is by trapping and relocating animals. This method still isn’t perfect because it causes stress to animals and can introduce new risks to animals if their social structures are disrupted, if they come into conflict over territory or if they have difficulty finding resources in their new environment.

Amy: Other threats that are more common for urban wildlife include animals being hit by vehicles, urban development infringing on their habitats and resources, and noise and light pollution which can disrupt their natural behaviours and communication.

Native wildlife

Threats to native wildlife in British Columbia and beyond

Amy: Wild animals, including those outside cities are also impacted by climate change which can affect their habitat, temperature regulation, resources like food and water, and behaviours like migration patterns.

Chantelle: One thing that a lot of Canada has been dealing with is forest fires. Temperatures are rising and precipitation patterns are changing, which means we’re seeing an increase in both fire-prone conditions and flooding at different times and in different areas. Forest fires and floods directly cause the deaths of animals who are caught in them. They also destroy habitats and displace animals, making it more difficult for them to survive and maintain their social dynamics.

Amy: Speaking of habitat destruction, there is natural habitat destruction, and there is also human-caused destruction of habitats like deforestation.

Logging is a major industry here in B.C. Although some considerations are in place for a few protected species, many animals like squirrels and birds end up losing their homes.

Logging roads that haven’t been decommissioned after use also make prey animals more vulnerable to predators.

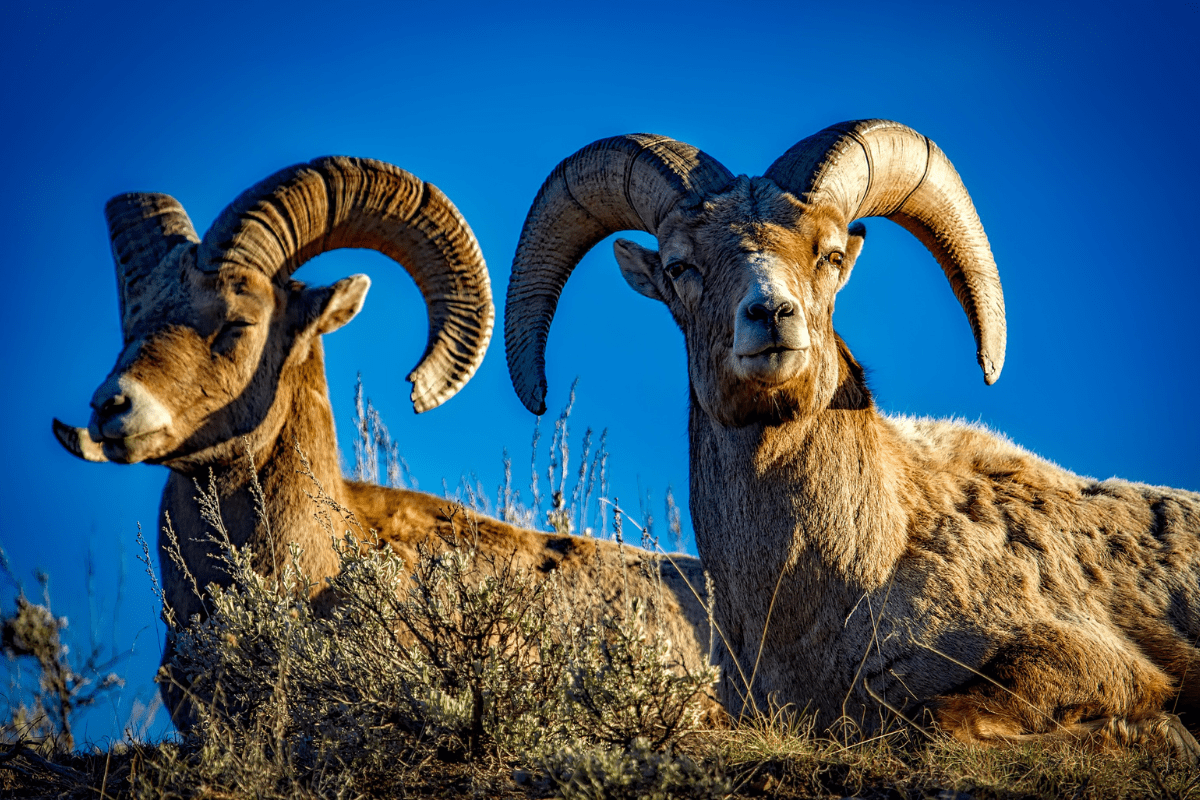

Particularly, caribou have been significantly affected by the destruction of forests and the creation of logging roads because it provides wolves easier access to the caribou, leading to declines in caribou populations. Rather than addressing the root issue, which is habitat destruction, the B.C. government has been carrying out a wolf cull since 2015 that involves shooting wolves from helicopters. So now we have a situation where both caribou and wolves are suffering.

We know that both caribou and wolves have complex dynamics, including unique family structures. When wolves are killed it impacts their entire family. Just like humans, they have the ability to feel loss and must grieve these sudden deaths as they struggle to survive.

How you can help native wildlife

Amy: To be an active ally for the caribou and the wolves, you can:

- Advocate for stronger wildlife protection laws, including the decommissioning of forestry roads and better forest restoration management

- Share about the importance of compassionate conservation, recognizing that well-being isn’t just about biodiversity, but about the well-being of the individual animal and their communities.

- Avoid having fires during fire bans, and carefully dispose of any cigarettes and be careful in the backcountry using machinery that causes sparks

Fishes

Chantelle: We can’t talk about wildlife behaviour without talking about the ocean’s most populous wildlife – fishes! You can check out our podcast just about fishes, but there are a few key points I’d like to touch on here. Fishes demonstrate many different behaviours, the same way that species on land do. Some live in schools, but others are solitary. There are even some interspecies friendships of fishes that are mutually beneficial. Fishes, just like mammals, end up having lice and benefit from grooming. Some fish travel long distances, while others exist in small habitats and focus on protecting their homes. There are more than 33,000 different types of fish species.

Threats to fishes

Amy: Some of the threats faced by fishes include fish farms, where diseases from captive fish populations can get into wild species. Fish farms are often densely packed, which don’t allow fish to swim and forage the way they would naturally.

Fishes are also threatened by pollution. While the physical pollution is a problem, such as plastics, some of the biggest harms include the waste product that runs off of intensive agriculture, such as keeping cows and pigs. This can cause harmful algae blooms in the water, which is often called ‘red tide’ for the different tone it gives the water. In areas with red tide, fish are poisoned and die. Animals like turkey vultures can be impacted as well as they eat the fish that have died from the harmful algae blooms.

How you can help fishes

Chantelle: The best and biggest impact that we as individuals can make is to take fishes and other animals off our plates. Consumption of animals for food is driving these complex issues that are causing significant physical suffering to both individual fishes and entire species.

Wild and exotic animals kept in captivity

Amy: The behaviour of animals that are kept in captivity varies from enriched and engaged, to, most commonly, bored and repetitive. Just like we seek out ways for indoor cats to have full enjoyment of their spaces, including building catios and providing different toys, treats, and play, wild animals need access to spaces and activities that make their lives worthwhile.

While the best thing is for wild animals to be free, sometimes they end up in captivity and don’t have the skills or capacity to care for themselves in the wild. Unfortunately, facilities that house wildlife in captivity often lack the staffing and capital resources to provide spaces for animals that ensure their needs are met. For example, some animals are not provided the opportunity to hide from public view, or the temperatures in their outdoor enclosure are too cold for their normal body temperature. Incidents regularly occur of people getting bitten, or animals becoming depressed and dying at ages far younger than their wild counterparts.

If you have observed animals in captivity, you know it can be a strange experience. Seeing the animals themselves can provide a sense of beauty, but juxtaposed against barren enclosures, cages, and pacing, bar licking, and other maladaptive behaviours, these spaces can feel downright uncomfortable. I once visited a facility where the bears were made to perform; that facility is still running today. Last year, when a bear died after 19 years of performing, the facility claimed that the bear loved making people laugh and was happiest in front of a crowd. It is common for facilities to anthropomorphize wild animal behaviours in order to make people feel at ease and buy into the experience they are seeking.

Chantelle: It’s so sad to think about and it’s easy for people to forget, because usually visitors to places like this will only be seeing the animal for a few minutes but this is the animal’s entire life day in and day out. I find it wild that animals are still being kept for use in entertainment, particularly the film and tv industry! I would have thought that would be phased out with the amazing technology we have. There have been a few really major films that came out recently where animals played a large role but thankfully they were all computer generated. Unfortunately, that’s not always the case and animals kept for performing are often kept in small cages and deal with frequent travel. Their lives are akin to that of research animals in terms of the degree of confinement, but even more stressful because their environment is constantly changing and they are around unfamiliar people.

Mobile exotic animal petting zoos are similar. The animals have to deal with frequent transportation, being kept in small cages, and being handled. Despite the risks around salmonella, reptiles are a popular choice for this because they are slow to get away. However, for them, it can be quite uncomfortable to be handled. Not only might it be uncomfortable, but it’s also very important for reptiles to regulate their own temperature; and the conditions they are kept and handled in do not allow them to do that.

Amy: While we know that it isn’t ideal to keep animals in captivity, the solutions are complicated. Zoos and aquariums try to argue in favour of letting animals breed as a way to exhibit natural behaviours, but then the off-spring often die or are forced into a life of captivity. Since such a sparse patchwork of laws exists for animals in captivity, their ability to express natural behaviours outside of breeding is equally sparse. Laws around wildlife in captivity are made at the provincial and local level. Advocating for these beautiful animals can include asking the provincial government to better protect them through limiting captive breeding, putting an end to using wild animals for any kind of entertainment, and asking the federal government to put very strict limitations on the importation of exotic wildlife.

Chantelle: Yeah, that’s an interesting argument because it feels very convenient that zoos will argue in favour of animals expressing their natural behaviours when it’s about breeding, which is something that allows them to draw in more people to see the new animals and keep making money, but not when it’s about moving the animals to a climate that’s more appropriate for them. It’s very important to look at those arguments critically and see how they’re being used to maintain the status quo and make more money rather than do what’s best for the long-term well-being of the animals.

How to help wildlife

Amy: We typically end these episodes on the question of what you can do in your own advocacy work to help animals. We’ve certainly touched on a lot of actions throughout the episode, but here are some of the biggest takeaways.

- Help wild animals stay wild by not feeding them

- When law changes around wild animals come up, speak with your representatives like your MP or your MLA about compassionate conservation and the importance of considering individual animals’ well-being

- Support and share ways of learning about animals that don’t involve keeping wild animals in captivity

Next episode

Please join us next month as we discuss the Vancouver Humane Society’s findings on the attitudes and benefits around plant-based eating!