What do you picture when you think of animals in science?

Perhaps you picture a researcher in the field studying the migratory patterns of wildlife. Perhaps you see a veterinary student learning to administer vaccines to a dog. Perhaps you picture a rabbit in a lab, eyes reddened and irritated from toxicity testing. In Canada there are many different uses of animals in research, teaching, and testing, ranging from noninvasive methods to some of the worst suffering animals endure. In this month’s episode of The Informed Animal Ally’s series on animal cruelty, the Vancouver Humane Society’s Amy Morris and Chantelle Archambault discuss the various ways animals are used in science, protections in place for these animals, and how you can help.

Note: This written discussion has been edited for length.

Overview of animals used in research, teaching, and testing

Chantelle: To start out, Amy, could you give us an overview of some of the uses of animals in science in Canada?

Amy: Animals are used in research, teaching and testing. Usually we talk about these as a group. I’ll start by talking about the ways animals are used in research. I want to preface this discussion recognizing that people come from a variety of backgrounds. We know there’s been human medical innovation that has involved animals in the process of how we’ve gotten to where we are today.

But we at Vancouver Humane Society are of the mind, based on all the available information we have, that we’re at a place now in society where innovation can move past animal use and research, teaching, and testing, and really be even more effective.

For a long time, we’ve had the three R’s, which have been advocated for for many years, which are replacement, refinement and reduction, as it relates to this area of research, teaching, and testing. But although these are spoken about, it still seems to be common practice for institutions and people involved in them to do what’s always been done rather than to consider innovation. The sad reality of this is that it’s costing billions of dollars, and more importantly, millions of animal lives unnecessarily.

Categories of animal-based science

Amy: We’ll highlight alternatives later on in the podcast, but I just want to start off with some facts about where things are right now. We know animal use can range from research with the intent to improve animal wellbeing to medical research for human benefit.

Universities have research divisions that include animals. These range from mild experiments, sometimes for the benefit of the animals, to extremely invasive experiments. And this research is managed through what are called animal care committees, where a group of individuals meet to decide whether and how the research can proceed. All these universities report their research data to an entity called the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC).

We’ll talk more about them later, but essentially, more than three and a half million animals were used by institutions that were accredited by the CCAC in 2021. It’s a huge number of animals.

That breaks down into five different categories.

We have studies of a fundamental nature in science relating to essential structures or functions, which is kind of a, a broad category that’s more than 50% of all animals used by CCAC accredited institutions.

Chantelle: This is also called basic research and it’s designed to find out more about the fundamentals about things like animals’ behavior, biology, and physiology. It can range from studying migratory patterns of wild animals, to studying the heart rate of Steller sea lions in captivity, to studying the effects of caffeine consumption on the brains of mice.

So it’s really a wide range of experiments and research.

Amy: Absolutely. Then the other 50% break down into:

- Studies for medical purposes, including veterinary medicine that relate to human or animal diseases or disorders;

- Studies for regulatory testing of products for the protection of humans, animals, or the environment;

- Studies for the development of products or appliances for human or veterinary medicine and education;

- Training of individuals in post-secondary institutions and facilities. That could be something like training a veterinary student to administer a vaccine.

So it’s quite broad, the many uses of animals.

Categories of invasiveness in animal experiments

And one other way that they can be categorized is the categories of invasiveness. The CCAC has broken these down into five categories, typically labeled A, B, C, D, E.

Chantelle: It’s already so concerning to hear that research is allowed to cause such a severe level of pain in animals, and again, I want to emphasize when we think about those types of testing, research, and teaching, we’re talking about huge numbers of animals being used and reported to the CCAC. It’s really enormous amounts of suffering going on.

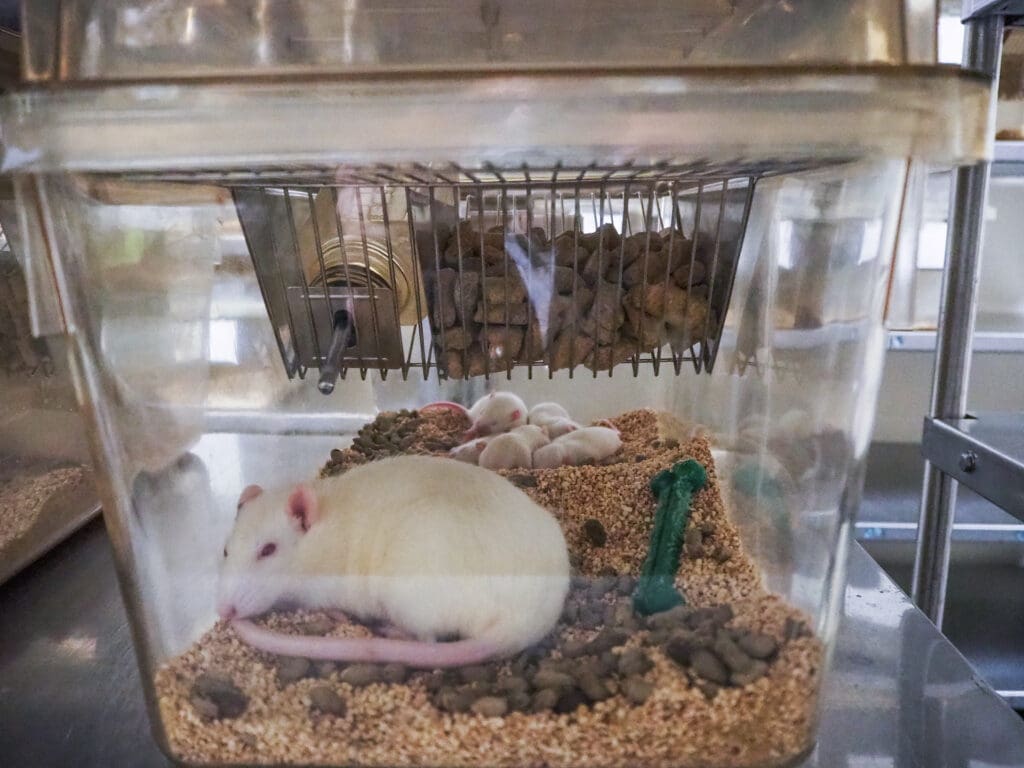

In the most invasive experiments, the animals used most frequently were fishes, mice, and rats. Other animals used for testing include dogs, cats, rabbits, guinea pigs; the same species many people consider to be part of their families who we know to be capable of love and complex social bonds, fear and pain.

Canadian Council on Animal Care

Chantelle: Now that we have that context for how animals are used in science, Amy, could you run us through a little bit more about what the CCAC is? What are some of the processes and laws in place to protect the animals used in science? And what are the limitations on protections for animals?

Amy: The CCAC, as I mentioned, is the Canadian Council on Animal Care. This is essentially an entity that is a non-governmental, non-profit type organization.

They don’t have any regulatory authority. All the institutions that are working with them are doing it out of a desire to be accredited.

They provide minimum ethical standards and required guidelines for the use and care of animals. In science, it is a requirement to get a Certificate of GAP (Good Animal Practice) in Canada. If an institution is going to receive federal funding for animal based products, they’ll have to get that certification.

Institutions that import animals to a lab environment also need to be in good standing with the CCAC.

I spoke a little bit about animal care committees before. To provide more context about what those are, universities have these in place and the CCAC guidelines dictate who needs to be on those animal care committees. They’re made up of researchers, chair and members of the public. They don’t dictate how the member of the public needs to be identified.

And that’s such a broad term, right? Because a member of the public could have a variety of thoughts and opinions on how animals could and should be used.

Every university does it differently. Some might post the position publicly. A more common route is that the existing committee members be asked to reach out to their networks and try to find someone who might be willing to be involved. They can’t have a conflict of interest, so it can’t be a spouse; that needs to be arm’s length.

There is a time commitment to it and it is an unpaid volunteer position. The role is pretty extensive; they’re reviewing protocols, renewals for protocols, of how and when animals can be used. There’s also amendments sometimes to protocols; you get maybe one to three projects a month to review. People will do maybe a few years of this kind of role and then move on, and they need to find more people to get involved.

At UBC for example, there’s one committee for all animal care projects, and then they distribute different protocols out depending on the number of members that there are. The members of the public are one of several committee members. It’s a great way to get involved in advocating for animals in a meaningful way.

People can reach out to universities directly to find out more about their selection process. It’s also a way to really deeply get an understanding of what it looks like to have different research and teaching and testing in universities.

Chantelle: Absolutely.

And that being said about all those requirements, it’s not a legal requirement to have CCAC accreditation. So there’s private institutions that are not CCAC accredited that also conduct research.

That’s unregulated in Canada outside of the Criminal Code and provincial animal protection laws. I don’t know of any cases that have been put forward for animal cruelty charges in Canada related to animal use in research. Employees are typically in an uncomfortable power hierarchy, so they wouldn’t be likely to report poor conditions, even if they aren’t happy with the way animals are cared for or are treated. There’s also agreements about nondisclosure and confidentiality that would make it more difficult to advocate for animals that are being kept in research and testing institutions.

You can take a look at the list of CCAC institutions on their website, and you can see that most of those are universities.

Toxicity testing

So now that we have a little bit of background on oversight and laws, we can delve a little deeper into what progress is being made to change the laws. One change on the table right now has to do with toxicity testing.

Amy: Yeah, this is a really interesting one because several years ago in 2015, Bill S-214 was introduced in parliament to legally phase out toxicity testing on cosmetic ingredients in Canada, so testing on animals for essentially cosmetic purposes.

It made it through Senate and then to the second reading of the House, which is very far along. It just needed one more reading to pass; and Parliament ended before it could receive that third reading. The reason that was even worse timing is that the bill already had support from all parties and from the cosmetics industry.

A letter that was submitted by Cosmetics Alliance Canada to the Senate and and to the House shared that animal testing to support the sale of cosmetics is no longer common in Canada.

This is for all intents and purposes something that just could easily pass and would prevent future uptake of testing on animals. We know now that this process is being restarted with a new bill, Bill S-5, that’s currently underway. Chantelle, could you share more about what’s happening with that?

Chantelle: Absolutely. It is really frustrating to see that that died during the election cycle. A little bit more background on toxicity testing. Toxicity testing tests the degree to which a substance affects an organism.

So for instance, the length of exposure of a substance like a new chemical, the route of exposure—whether it’s toxic through contact to the skin, inhalation, injection—and the concentration of a substance.

As you can imagine, it results in pretty severe suffering. It’s considered the most harmful use of animals in science. It commonly causes the most severe level of suffering and it impacts about 90,000 animals per year in Canada.

Testing the substances involves forced ingestion, forced inhalation, and skin and eye irritation. If animals don’t die as a result of the experiments, they’re typically killed afterwards. This is pretty horrific.

The US and the EU have already made commitments to phase out toxicity testing. The federal government in Canada made phasing out toxicity testing a campaign promise in the last election.

It is something that it makes sense as the next step in progress for animals in this area. Bill S-5 is an amendment to the Canadian Environmental Production Act (CEPA). That’s the law that governs how we assess chemicals and processes by which we test that substances won’t harm the environment and human health. Part of that process is toxicity testing, the testing to determine toxic effects of a certain substance; for instance, if a new ingredient was going to be used in a product.

Part of Bill S-5 aims to address toxicity testing on animals.

The previous bill died before being passed when the election cycle happened. This bill was reintroduced to Senate, and Senate made a lot of amendments that actually strengthened the protections.

Now it’s gone back to Parliament again where the standing Committee on Environment is going to review it. Animal Justice has been working with government officials to make amendments to the bill, working within the bounds of the law that’s on the table to make as much impact as possible for animals.

The goal right now is to make animal testing the very last resort when absolutely no alternatives are possible.

Amy: Something I think is really interesting about this is some other countries that have passed laws in this area are not allowing products that are made of components that are tested in other countries. That’s sort of the gold standard for a law like this, where you’re not just outsourcing the problem of testing on animals to another country. I’m really curious to see whether this bill ends up including some elements of that; whether it’s an end to that practice altogether or whether it allows for loopholes where the testing can just happen in another country.

Chantelle: That’s a good point. And there are a lot of alternatives that are available now that would make that unnecessary in most cases.

Alternatives to the use of animals in science

Amy: Something that’s really important to consider when talking about alternatives; it’s not just the animal testing piece, but it’s also just thinking about the types of animals that are used.

There are live animals that are used. There are also animals that are purposely bred to be used for dissection in education.

There are a number of technological innovations that make it possible to learn about biology without intentionally producing animals to be killed for dissection or used for various forms of research, including testing.

The Society for Humane Science shares that although 79% of science teachers in British Columbia still do dissection with their students, non-animal alternatives to dissection have been shown to be just as effective or more effective in terms of how well they help students meet their learning goals, and they even save time and money. They have a great blog post with so many non-animal model alternatives that cover a wide variety of species.

Any teacher anywhere can use those resources and move to a place where dissection isn’t costing animal lives.

Chantelle: I can see how requiring dissection in some schools would actually be a deterrent for people who would be more prone to using animal-free methods. Anecdotally in my own life, I’ve seen people who have dropped out of the biology stream of science specifically because dissection was a requirement in their school. So it is interesting to see where the future will go and what kind of individuals that will draw into the field.

Effectiveness of non-animal models

Chantelle: Jumping back to testing methods, one of the main arguments I’ve heard in favor of animal testing is that it’s necessary for medical progress. There have been life changing medications developed in the past through methods that used animal research, like penicillin.

You’ll still hear people say, “I understand the harms that animal research causes, but I personally have a loved one with a life threatening condition, and we need to find a cure for that.”

In reality, those two perspectives, the one advocating for animal wellbeing and the one in favor of making progress for human medical treatments are becoming more and more aligned.

While there have been developments in the past using animal based methods, they’re few and far between, and now that process might actually be slowing medical progress.

Amy: Yeah, absolutely. The film Medical Illusion, produced by documentary filmmaker Gary Charbonneau, covers how ineffective animal use is and the different alternative technologies that are available.

It’s estimated that around 95% of drugs that are shown to be effective in animals failed to be effective in human clinical trials. That failure rate is enormous. You don’t accept that failure rate in any other area; yet somehow because it’s animal lives our society is discounting that.

In some cases, institutions are testing on animals for diseases that don’t even occur naturally in those non-human animals. They have to be artificially created in the animal creating an unrealistic disease process. And then that results in drug responses that are entirely different than that what would occur in a human.

The scientific experts in this film, Medical Illusion, advocate for investment in technologies such as more personalized medicine, such as tissue engineering, and bioprinting technologies such as 3D organ printing. The one that I think is really interesting is organs on a microchip.

I’m really excited for a future where these technologies are the go-to for all scientists.

Chantelle: Absolutely. And it’s so exciting to see that there’s also medical professionals advocating for the same thing. Dr. Charu Chandrasekera at the Canadian Centre for Alternatives to Animal Methods is doing a lot of great work in this area.

It would really benefit everyone to move away from animal testing. Of course, we know that the animals and those who care for them would benefit by not having testing required on animals, but also the institutions doing this research and the medical community as a whole.

When you consider the investment that goes into trying to make medical progress, each new medication represents a massive investment of time and money—10 years and more than a billion dollars on average that go to waste if a drug fails in a human clinical. That’s a huge investment trying to find necessary cures for life changing conditions and diseases, only to fail at the human clinical trial stage.

One example is more than 400 human trials have failed for Alzheimer’s. But Alzheimer’s has already been cured in mice because their biology is the basis for so much animal based research. Requiring animal testing means that treatments that could be effective for humans might be thrown out because they aren’t effective for animals that they aren’t even intended to be used on. Who knows how many medications that would’ve been life saving for humans have been missed because they weren’t safe for mice?

How you can help

Chantelle: We always like to talk about what our audience can do to advocate against animal testing. What are some ways that people can advocate against animal testing, research and education?

Purchase products not tested on animals

Amy: An easy thing to do is to purchase products that weren’t tested on animals.

To know for certain that a product’s ingredients were not tested on animals, and that there are no animal ingredients (such as gelatin) used as well, PETA’s Beauty Without Bunnies program accredits more than 5,900 different companies. Their website is really helpful way to learn more about that program.

Leaping Bunny is another program that accredits companies. They only accredit based on companies that don’t test on animals, which means accredited products might still contain animal based ingredients. When making purchasing decisions, it’s important to review the ingredient list to ensure that no animal products like gelatin or coloring based on animal bodies is included in that product.

There’s some trade offs of these two programs in terms of how they accredit. Ethical Elephant created a graphic to help distinguish the pros and cons of those different programs.

Chantelle: Absolutely. That’s a really actionable step that everyone can take every time you’re buying a product.

Support phasing out toxicity testing in Bill S-5

Chantelle: Another step is contacting your MP to support phasing out toxicity testing. Bill S-5 is in consideration at the House of Commons right now, and that could make a huge impact for some of the most severe suffering that happens for animals used in science.

You can visit this Animal Justice Academy video for more details about the bill and about toxicity testing in general. You don’t need to be an expert to speak with your MP; you can call or email them and just let them know that you want to talk about Bill S-5 on CEPA, and you want to ensure that they support reducing the unnecessary suffering of animals. Science is evolving; other countries have already made commitments to phase out toxicity testing. This is a really attainable goal that Canada can make to have a significant impact in the lives of animals.

Advocate for alternatives in education

Amy: Absolutely. And I think another really big way that we can have impacts are at different levels of educational institutions. This could be anywhere ranging from high schools where dissection is happening to universities where you could join an animal care committee.

If you’re someone who has the capacity to volunteer your time, joining an animal care committee is a way to make a tangible impact for animals. You can reach out to your local university, find out if they’re conducting research on animals and ask more about their selection process. Get involved in making sure that research is consistent with guidelines and regulations, and even more, recognizing that there’s a a place for someone to serve as an advocate for animals.

The other role, if you have kids or even if you don’t, is reaching out to high schools and finding out what programs are being used for dissection. See if you know you can meet with a biology teacher and share about the different alternative models and find out what the barriers are to them adopting those models. Certainly every single one of us can become an individual advocate in communities because those decisions are being made on a teacher by teacher basis.

Chantelle: Absolutely, and this is such a rapidly developing field that there’s so much space for impact on the short term and the long term for animals.

Next episode

Now that we’ve gone over all these laws around animal cruelty over the past six months, we’re going to be wrapping up the year next month with a discussion on how the laws and regulations are enforced. Until then, if you’d like to share your thoughts on this topic or any other topics that we’ve discussed already, please reach out to the Vancouver Humane Society on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram.