How do bills become law in Canada?

Have you ever seen an action advocating for a new law in Canada and thought, “Didn’t that bill already pass?” The process for introducing a new bill and voting to make it law is long and complex; but knowing how this process works gives us power to make our voices heard.

This episode will break down in simple steps the types of bills in Canada, how a bill becomes law, examples of bills that have passed to improve life for animals, what happens when a bill doesn’t pass, and how you can make a difference at each stage of the process.

Note: This written discussion has been edited for length.

Introduction

Chantelle: Right now, we’re in the middle of our series looking at a macro view of animal protection: How does advocacy make change and where does Canada stand on the world stage when it comes to animal protection?

This month we’ll be zooming in a little bit on a topic that I think causes a lot of confusion, which is the process of how federal laws in Canada actually come to be.

If you’ve ever seen a headline like: “The Bill to ban live horse exports for slaughter from Canada passes at the House of Commons”, and then later heard about that bill dying before becoming law, and thought to yourself, “Didn’t that bill already pass?” This episode is going to break down the different steps of the process in a way we hope will be engaging and understandable.

We’ll also look at some examples of bills that have passed to improve animal protection and what happens when a bill doesn’t pass in time or is voted down, as well as how you can advocate at each step of the process.

Amy: I’m excited about this one. I think it can be really confusing about what is going on with these bills, and we send out action alerts at many different stages, and I imagine people are like, “What is going on? I’ve already spoken to somebody about this.”

Hopefully this will clarify why it’s so important to advocate at a number of different stages, because the audiences change of who we’re advocating to and who we need to give the thumbs up.

Types of bills

Amy: I’ll get us started with the types of bills that we have.

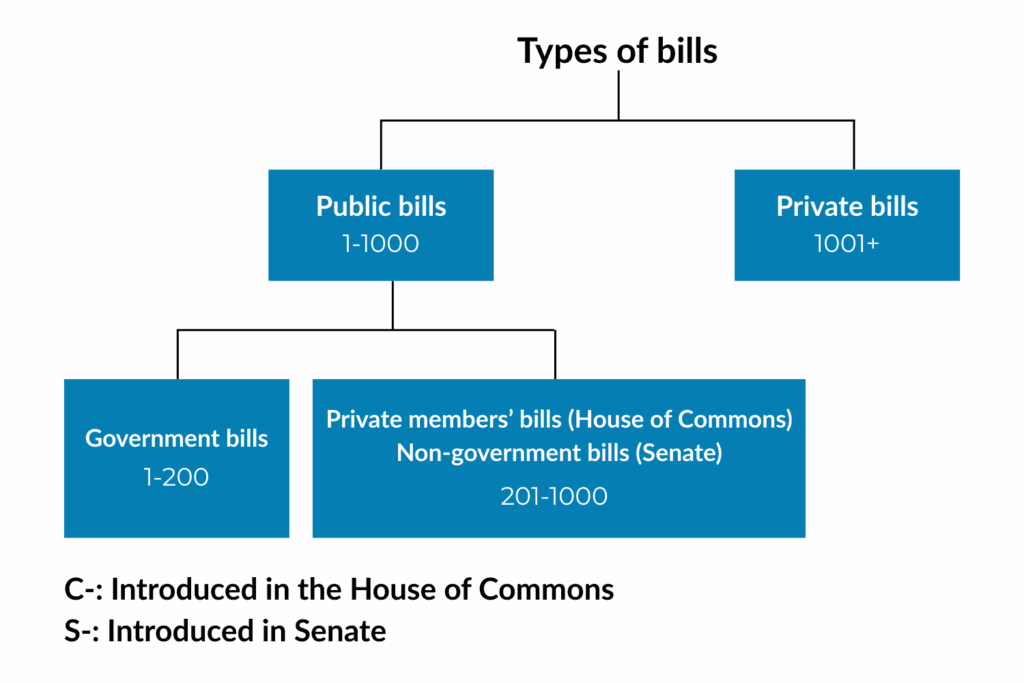

A few types of bills in Canada can be broken down kind of into like a tree diagram.

If you’re following the updates of a bill as it becomes a law, you’ll notice that there’s a code associated with each bill. For instance, the bill to ban captivity of cetaceans like whales and dolphins was commonly called the Free Willy Bill, but the official name was S-203.

If you know the breakdown of the different types of bills, you can actually tell what type of bill it was based on the code.

Public bills vs. private bills

Amy: Overall, there are two main categories of bills in Canada that tell us what type of matter the bill is dealing with. There are public bills (numbered 1 through 1000 in the bill’s code) and private bills (numbered 1001 and beyond)

Private bills have a very specific purpose of granting special powers, benefits, or exemptions to a person or group.

Anything involving animal protection is going to fall into the category of public bills, which is the type of bills that deal with matters of national interests, like budget, industry or social issues.

Public bills: government vs. private members’ bills

Amy: And then you take this category of public bills and you further break that down into a bill that comes out from the government or private member.

That tells us who is introducing the bill and their level of involvement with the government.

Government bills are introduced by a key decision maker in the government; when we say that, that means the party in power. They are bills that are considered a matter of public interest, and they represent the direction the elected party is prioritizing.

The people who can submit a government bill are a parliamentary secretary, the government representative in the Senate, or a cabinet minister. These are all key decision-makers for a government.

A cabinet minister is an elected MP selected by the Prime Minister to be part of the country’s key decision makers. The cabinet is almost always made up of members of the same party of the Prime Minister. I would say in recorded history, that’s the case. And so for instance, our current Prime Minister, Prime Minister Mark Carney is Liberal and the cabinet that he has chosen is all made up of elected MPs from the Liberal party.

An example of a government bill would be a decision to implement budget changes in the country like Bill C-47, a budget change bill from 2023.

Government bills are numbered between 1 and 200.

Private members’ bills (House of Commons) /non-government bills (Senate) are simply public bills that are introduced by a member of Parliament or Senate who is not one of the key decision-makers that we just listed.

This means that this type of bill can be introduced by someone from any party as long as they have a seat on Parliament or in the Senate. Private members’ bills can deal with issues of public concern, but they can’t change taxes or how government funds are spent. They’re numbered from 201 to 1000.

Bills introduced in the House of Commons vs. Senate

Amy: We can have bills that are introduced in the Senate, and those are bills starting with an S, and they have bills that are introduced in the House of Commons, starting with a C.

Even though where they’re introduced is how the bill is labeled, they all need to pass through both the Senate and the House of Commons to become law.

And, and just a reminder, Senate is appointed in Canada and the House of Commons is elected by voters.

How a bill becomes law

Chantelle: Thank you so much for that overview, Amy. Every bill does go through both the Senate and the House of Commons, and they all go through several readings at both of those houses. I’ll break down what each of those readings means. When you get updates from us, usually it’s after each stage of the readings at the Senate and the House of Commons.

First reading of a bill in Canada

Chantelle: The first reading just means the bill is being introduced in either the Senat or the House of Commons. It is named and it’s made available to the public.

There’s no debate at this stage and there’s no vote. It’s just being introduced.

Second reading of a bill

Chantelle: At the second reading, now that the rest of the MPs or Senators have been introduced to the bill and they have had a chance to read it, they also now have a chance to debate it.

Even though it’s called a second reading stage, this can happen over multiple sessions if there’s no decision made.

There can be a vote to reject the bill at this stage or at any stage after this, or a vote to move the bill to the next stage. So it can technically move right to a third reading, but it’s usually first moved to a committee to study it and make amendments.

Committee stage of a bill

Chantelle: At the committee stage, a smaller group from the House of Commons or Senate will take a closer look at the bill.

It’s usually referred to a standing committee that has a specific focus in the bill’s subject matter. So for example, if it’s a bill about farmed animals, it would go through the Committee of Agriculture and AgriFood at the House of Commons and the Committee of Agriculture and Forestry at Senate. But some bills can go to a legislative committee instead, which is just a group created to consider a specific law.

The committee goes through the whole text of the bill and they propose amendments to specific clauses of the bill if they choose to.

After they decide what changes to make to the bill, if any, they vote on the bill as a whole. The committee cannot reject the bill outright, but if they don’t like it and they don’t want it to move forward, they can choose to recommend that the bill be dropped at the next stage during the reporting stage.

Reporting stage

Chantelle: The reporting stage is when the committee reports back to the larger group on their recommendations.

If it’s in the House of Commons, the other MPs can suggest additional changes here. The Senate can suggest additional changes at the third reading.

After the report, the house votes on the changes if there are any, and finalizes the bill for the third reading, which is the last step in the house.

Third reading of a bill

Chantelle: The third reading is the final debate on the finalized text of the bill. The House of Commons or the Senate decides if they want the bill to be adopted. If they choose to have the bill adopted and they vote yes, the bill moves on to the next house to go through this whole process again.

Or, if it’s already been through both houses, then it moves on to the the final stage of royal ascent. The houses have to talk to each other if they have made amendments to the bill; they can’t just make amendments and not speak to each other afterwards. If a bill was introduced at the House of Commons and it passed by our elected officials, and then the Senate wants to make more amendments, they have to reach back out to the House of Commons until they can agree between the two on what the final text of the bill is that they want to use.

How a bill becomes law in Canada: Royal Assent

Once both houses pass the bill, it moves on to receive Royal Assent. Canada is a Commonwealth nation, so the bill is signed by the Governor General or one of their deputies who represent the King of the UK in Canada.

In theory, the law could get stopped at this stage, but it won’t in practice, because that would violate constitutional conventions by interfering with the decisions of elected officials.

It’s really just a formality, but it is necessary for a bill to become law.

That was a lot of information and it was kind of abstract, but we’d love to share a few examples of what this has looked like in practice for different animal protection bills.

Amy: Yeah, it’s so interesting. I mean, even the reality that if changes get made in one place, then the other team has to approve those changes. I imagine there can be a lot of back and forth that happens even in that. So it’s amazing anything gets passed.

Certainly it has to do with how many people are in favour of a certain way of thinking.

We could call it a party, but it’s even beyond that. When we think about the Senate being appointed, what is the general sort of attitude of the Senate? Even if a party is elected into the House, if the Senate has a different leaning of how they think things should be done, they could consistently hold up bills from being passed.

I don’t think they necessarily do, but it’s interesting to think about how our political system kind of like chugs along.

Chantelle: Yeah. And it does kind of explain why it takes so long to make progress in this country when we look at how long the process actually is.

Amy: Yeah, absolutely.

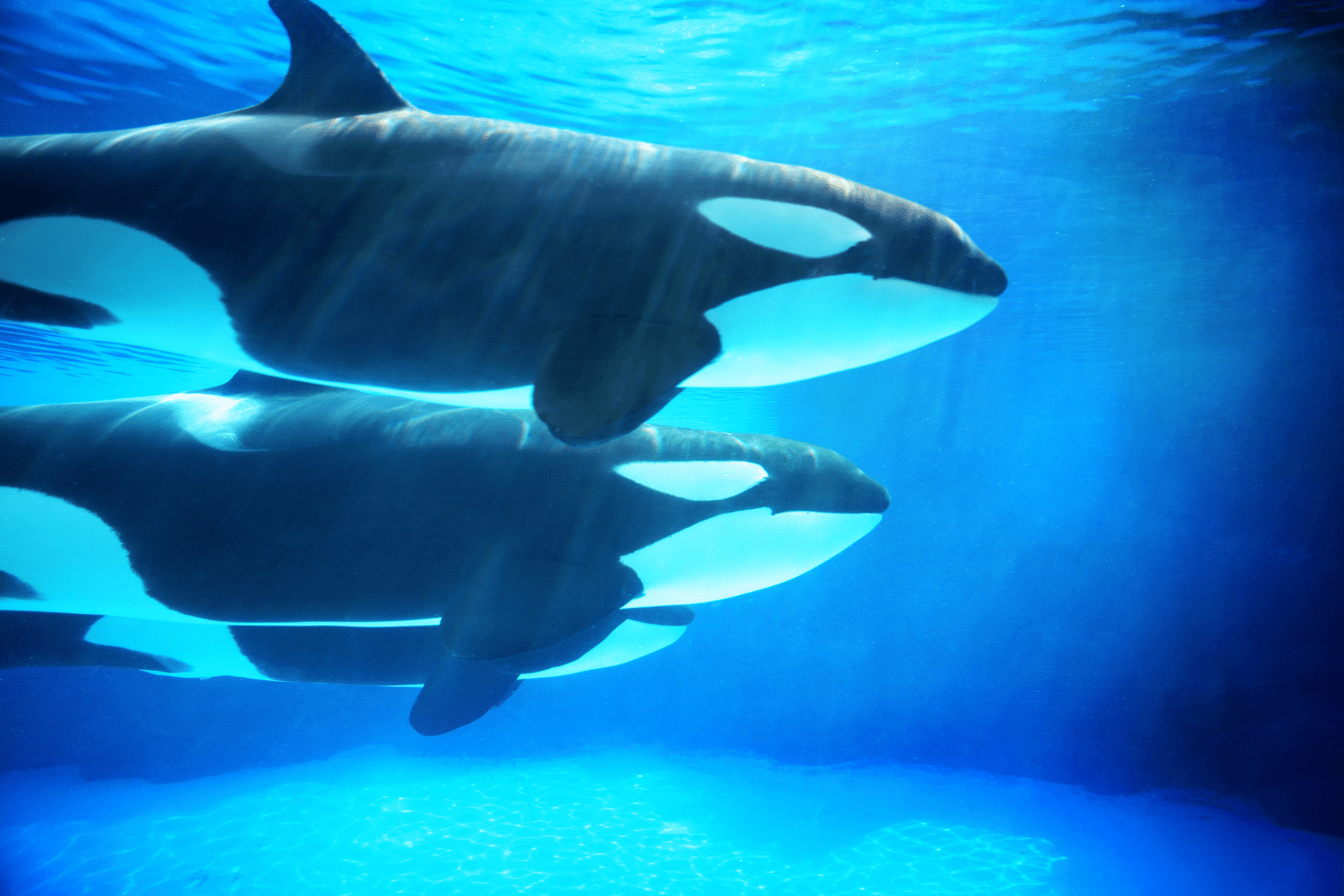

Bill S-203: The “Free Willy” bill

Amy: I briefly mentioned earlier about Bill S-203, also known as the Ending the Captivity of Whales and Dolphins Act, or more commonly as the “Free Willy” bill.

This one is a really interesting one for me because I got to sit on a Senate committee hearing and I was in the room with all of the Senators talking about it. I even witnessed one of the Senators getting text messages from folks who maybe were on the opposing side of the bill and reading out those text messages, which is kind of questionable activity.

And so this one’s personal for me. So you can tell by the code that this was a non-government bill and that was introduced by the Senate because it started with an S.

Like a lot of non-government bills, it was introduced because of pressure from the public. Many individuals across Canada had been speaking out about how whales and dolphins were suffering in captivity. The knowledge of the sentience of cetaceans was irrefutable.

It could no longer be justified to keep these animals for entertainment, so organizations including the Vancouver Humane Society, Humane Canada, Animal Justice and World Animal Protection ran advocacy campaigns on this both locally in individual jurisdictions like Vancouver and Toronto, and also at a national level.

Humane Canada worked with Senator Wilfred P. Moore in 2015, just an incredible Senator. I recommend looking into that individual and some of their quotes.

It took three years from 2015 to 2018 for the bill to move through all the stages at Senate. Then luckily it did move fairly quickly through the House of Commons between October 2018 and June 2019, and received Royal Assent just 11 days later.

It’s quite a bit easier to advocate for a bill to pass at the House of Commons, especially for something like that, having widespread public support because the MPs are accountable to their constituents who voted them in, and they’re generally hoping to be reelected.

The reason that this bill did move through was really consistent internal advocacy between Wilfred P. Moore and other Senators, and really recognizing the value of these beautiful animals. It can’t be understated how important the internal advocacy is in these stages of the processes.

And certainly, although Senators are appointed, they can still be contacted by members of the public, and so advocacy makes such an impact to keep these things moving, especially with politicians or Senators who are on the fence. Hearing from people makes it less intellectual and more of demonstrating the public demand.

The final text of the bill that we’re talking about makes it illegal to capture or keep whales, dolphins, and porpoises in captivity, except those that were already in captivity when the law came into effect, and a few other exceptions, like research with a license from the province and rehabilitation.

This is one we were really grateful for.

Chantelle: Yeah, absolutely. This was a huge victory that really shows that when we come together and keep pushing for change, we can really motivate a government to make it happen.

Of course, there are still many other animals being kept in captivity at zoos and aquariums who, like cetaceans, aren’t suited to have a good full life in human care, and we keep advocating for better protections across all wild and exotic species.

But this was a huge win for cetaceans.

Amy: Absolutely.

Bill C-47: Budget bill bans cosmetic animal testing

Amy: Another example of a win for animals that used a completely different approach is the ban on cosmetic testing on animals, which passed as part of a big omnibus bill, which was C-47.

And for a bit of history of this, the ban on cosmetic animal testing was a private bill at one point that essentially died and then it got revived again.

Once it was revived, it became a government bill. There were enough lobbying efforts that recognized that this bill shouldn’t have died, that it should have gone through. And so the government was willing to take it on, which is amazing.

It was introduced in the House of Commons as they were implementing changes to the budget, so it did represent a major part of the government’s plan and priorities.

Something to note of why the government took this on is that there were people from the cosmetic industry that wanted this bill to pass, so there wasn’t opposition to it the way that there can be with some bills because the cosmetics industries were saying, “Yes, please pass this bill.” There was no one really opposed to it.

Some of the changes that were looped into the bill were amendments to the Food and Drug Act, and one of those was essentially a ban on animal testing.

A mix of things went into this strong advocacy from organizations across Canada to include a ban on animal testing in this bill.

As I shared, it’s a relatively uncontroversial issue. Stakeholders from the beauty industry were on board as well as the public and animal protection groups. And the Liberal party even made a campaign promise to end cosmetic testing on animals as soon as 2023. So it made sense to include it as part of one of their government bills.

That ban went through the same process as many bills do, and took effect in December, 2023 once it was passed by both the House and the Senate.

Chantelle: It’s so interesting to see the different paths that we can take to improve federal policies because those are two successful bills that did become law that took such different paths.

I am really grateful that they did end up both passing. But not all bills make it that far.

What happens if a bill doesn’t pass?

Chantelle: Unfortunately, if a bill is voted down at any stage, or if it doesn’t make it all the way through the process and receive Royal Assent before an election is called, and Parliament is dissolved for the session, then that bill dies and it stops moving through the process.

If people want to reintroduce it, it needs to start again from the beginning.

Bill C-355: Banning horse exports for slaughter

Chantelle: One example of this that we’ve spoken a lot about is Bill C-355, which was the bill to ban the export of live horses from Canada for slaughter overseas.

Banning this industry was a campaign promise from the Liberal government in 2021, and it was also included in a mandate letter from former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to the Minister of Agriculture at the time, Marie-Claude Bibeau.

So, in theory, it could have been included as part of a government bill. It was an election promise, just as ending cosmetic animal testing was. But instead it was brought forward as a private members’ bill, which can pass, but they have a relatively lower rate of success.

Amy: One of the reasons for that is the way time is allocated in the House is that government bills always get the first order of business, and then essentially the private members’ bills get the last little bit of time, and there’s lots of them, and they get selected at random.

So there’s just like basically drawing a number out of a hat: Okay, you get to do your bill today. But with so many of them, it often takes months for a bill to even get first reading, second reading, et cetera. And so that limits significantly the funnel of private members’ bills ever being passed.

Chantelle: That’s a great point. Any private members’ bill passing is a huge feat and this one simply didn’t.

Why is Canada still exporting horses for slaughter?

Chantelle: Bill C-355 was introduced by Liberal MP Tim Lewis. And it did actually end up passing through all the stages at the House of Commons. So our elected officials said, “Yes, we agree with Canadians. This is an industry that is cruel and should end.”

But when it got to the second reading at the Senate, when it’s put to a vote, it kept getting stalled. It was debated in May 2024, and then it was not picked up again until November.

There was a lot of public pressure in between those two debates. And there were certain Senators essentially dragging their feet on this bill, questioning the integrity of advocates and muddying the waters with unrelated issues.

A few things came up in debates, and you can actually read the debates if you look up Bill C-355. It’s all public information. If you look through the process, you can see the transcripts of what was said in Senate.

The first time it went to debate, one Senator brought up how the bill might affect lobster fishing in Atlantic Canada.

Then over the summer and early fall, two exposes came out from Animal Justice and advocates from Japan who revealed what happens on the receiving end of horse exports. They found most horse shipments actually exceed the legal limit of 28 hours without food, water, or rest that our regulators allow by the time they make it to their final destination; because we really only track until they make it onto the tarmac on the other side. But by the time they actually make it to where they’re going to be staying and they receive that food, water, rest, it’s usually over 28 hours.

And they also found that horse deaths on these flights were being vastly under-reported by Canadian regulators.

In the follow-up debates, there was a Senator who kept questioning if those reports could be trusted. Senator Don Plett was very vocal about this, and after Parliament was prorogued, he even wrote an op-ed that made a lot of misleading claims about horse exports.

So again, this is a small number of Senators who were appointed, not elected, who were holding up a bill that would save thousands of lives, and that about two thirds of Canadians agree with.

How “getting in the weeds” distracts from the big picture

Amy: One of the other things that’s really interesting about this is it gets into so much of the weeds to say, “Are those reports that it’s beyond 28 hours accurate,” when what we’re talking about are animals that are being subjected to a really horrifying series of steps.

Of being transported, put in tiny crates, flown on a plane still in tiny crates, brought to a slaughterhouse, and then slaughtered. The amount of stress that they go through is enormous. Whether that’s 27 or 28 or 29 or 40 hours, the horses are still suffering significantly. That was the main point.

So what ends up happening is you have these sort of industry-supported senators, like Senator Don Plett, who take the opportunity to break an argument down into tiny distracting steps that then take away from the overall concerns.

And to be fair, in what I mentioned earlier from S-203, Don Plett was the same senator who was receiving texts from Marineland during the Senate committee hearings.

So there’s also a pattern that was with this individual of supporting industry, whatever it is, in causing harm to animals. And I’ve learned recently that this senator is retired, so that’s good news and hopefully we see more kind of animal-aware and thoughtful senators taking leadership in the Senate as we move forward.

Chantelle: You’ll see this both in Senate and anywhere you’re talking about important issues.

One of the really common methods that people will use to try and counter your argument is breaking it down into a lot of minute counter-arguments. They’ll say them all back to back and they’ll make a lot of claims. Some of them may be true, some of them not true.

That’s called a “Gish gallop”, and it has been used historically by people who are debating in bad faith. It ensures that if you were to, one by one, accurately and thoughtfully address each one of those claims, you would run out of time.

So you can’t address all of their claims and all of the falsehoods that they’ve brought forward and say what is misleading and what is not. And then a lot of people will then come back and say, “Well you didn’t address this part of my argument.” That is why it’s a bad faith kind of argument.

Delays mean ban on horse exports for slaughter will need to start from the beginning

Chantelle: The bill went through four debates in its second reading, and then Parliament was dissolved before the election, which means that it will need to be reintroduced and it will need to start the process from the beginning.

How to advocate at each stage of the law process

Another way to advocate: Work with the ministries

Amy: And certainly, there are a lot of different ways to go about making change with government.

Working with the elected officials and appointed officials is one step.

Another way of making change is working directly with the ministries. The ministries are putting research and information together that works its way up into the government as recommendations to the ministers, who then can put them forward as government bills.

And so when you do that, you’re essentially avoiding all the plagues that come with a private members’ bill.

That’s the strategy that Humane Canada, who represents animal protection organizations across the country, will be focusing on with this new cycle, is how do we get information into the ministries themselves so that the ministries then put that forward into government bills and it’s much more likely to pass. So that’s something to stay tuned.

We as citizens can also contact the ministries. We’re not limited to contacting elected officials, and so that’s also something to consider when doing advocacy is what is the best avenue for getting change across.

Step 1 of engaging with the law process: Get to know your MP

Amy: And just to share a little bit more ways that any individual citizen can engage with this whole process. The first one is just get to know your MP, because no matter where they lie on the political spectrum, they are tasked with representing you once they’re elected.

You can give them a call or send them an email and share the issues that are important to you that you’ve learned about.

And that can be a number of issues. That doesn’t have to be all animal related. It’s just a way of saying, “Here’s what I care about and I’m one of your constituents.”

Introduce a parliamentary petition

Amy: If you want to get a bill forward on the agenda, you can work with an MP to introduce a parliamentary petition, and so you can create one or you can sign one on the Parliament of Canada website.

If an online petition gets at least 500 valid signatures, the government has to respond to it within 45 days. They do a written response, which is pretty ideal in that it becomes an issue that the government now considers something that is important.

It’s a great way to get an issue on a decision makers’ radar. Petitions that get a lot of support from Canadians are more likely to lead to policy proposals.

When a bill is introduced: Contact your MP or Senators from your province

Amy: Once a bill is introduced, if it’s in the House of Commons, you can contact your MP to share why you do or don’t agree with bill, and ask them to vote in alignment with their constituents’ values.

If it’s in the Senate, you can also contact the Senators from your province.

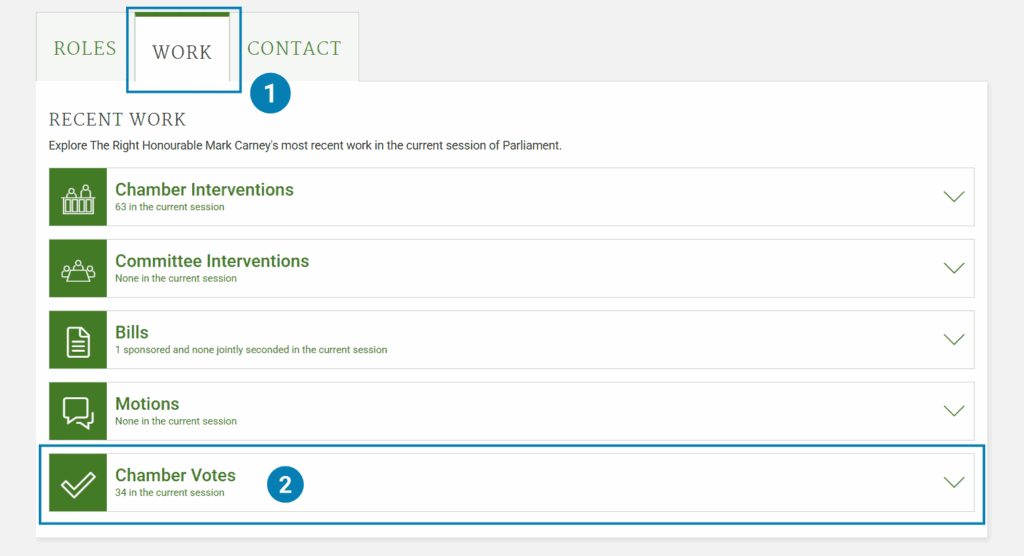

See how your MP voted at each stage and follow up

Amy: You can also follow along with the progress of a bill if you’re on the Vancouver Humane Society’s mailing list. We often share updates on relevant animal welfare bills. Anything that’s happening nationally, we want to make sure you’re aware of in addition to all the local work that we’re doing.

And then after each stage of the bill, you can see how your MP voted and you can even reach out to them and thank them or share why you feel they should change their position for the next voting opportunity.

Chantelle: Yes, absolutely. And you can look up any bill name, as I said before, on the Parliament of Canada website.

And in the details of the bill, you can see the results of the recorded votes, so you can see what your MP voted on the bill. You can sort those results by province or by political affiliation and see all the people that voted yay or nay. The MPs usually vote along party lines, and I certainly look at that data for important issues to me to see which parties are voting in alignment with my values.

See how your MP has voted on past issues

Amy: You can look up your specific MP to see how they voted on past issues to inform how you engage with them, recognizing that some issues they may be more willing to engage with than others.

Follow along with Humane Canada

Amy: It’s good to stay involved with Humane Canada’s messaging because they are that national body doing national work, and there’s a number of bills that didn’t make it through in the last session. They’ll be working on getting policy change on those.

Certainly one of them is related to housing of exotic animals. That one’s called the Jane Goodall bill. A lot of work was done on that one before an election was called, and so they’ll be coming up with a new strategy for how to get that through.

Honestly, the most important part is having individuals write in and show that they care If it’s just organizations that are representing individuals, the response from elected officials is far less engaged than if they’re hearing from many different supporters.

Takeaways

Chantelle: To sum up today’s conversation, I think it’s safe to say policy change is a long game, but change is certainly possible and we are making progress.

We are most effective when we’re strategic about:

- What change is possible right now?

- How do we bring people together to put public pressure on decision makers?

- The timing of making those changes: What commitments have been made by the government in power or what is happening in the world to bring attention to these issues?

Next episode

Please join us again next month as we talk about about the ways animal advocacy intersects with social justice and community care, and how those sectors can work together to make a kinder world for both people and animals.