Animals dying in transport, bred without oversight, and sold in deli containers. What is happening in Canada’s exotic pet trade?

In this month’s episode of the Informed Animal Ally, the Vancouver Humane Society’s Chantelle Archambault and Amy Morris discuss Canada’s exotic pet trade, from breeding or capture to selling and keeping, as well as the laws and loopholes failing to protect animals.

Note: This written discussion has been edited for length.

Impacts of the wildlife trade

Chantelle: Today we’re going to continue looking at Canada’s place on the world stage of animal protection by delving into a topic that impacts animals, both at home in Canada and around the world: the wildlife trade.

While this term “wildlife trade” can be used to discuss the buying and selling of both live animals and products made from their body parts like elephant ivory, rhino horn, and animal skins, in this episode, we’ll specifically look at the transport, keeping, and breeding of live non-domestic animals for uses like the exotic pet trade and display in events like mobile petting zoos.

Captive non-domestic animals have complex needs like wild animals

Amy: Before we get into what the wildlife trade looks like in Canada, I’d like to give some brief context about why this is such an important topic.

The wildlife trade or exotic pet trade involves animals that are not native to Canada. They’ve not been domesticated, which means they have their wild instincts, including a fear of humans.

They have really big behavioural needs. Those include:

- exploring large spaces,

- climbing,

- accessing the right temperature environments,

- being able to stretch their bodies out in such a way that feels good for them.

That happens even if they’ve been bred in captivity.

Exotic pets are not “beginner pets”

Amy: A lot of exotic animals like turtles and lizards and snakes are often marketed as beginner pets; and so people aren’t really being told how difficult it is to provide care for these animals.

More than two in five people with exotic pets say that they bought them on impulse, and almost half are saying that they did less than a few hours of research on how to care for the animal that they’re buying (Stratcom, 2018, Exotic Pet Ownership Qualitative Research).

So what that means is they’re essentially being sold to families with young children and people with limited time and resources who don’t really know that these animals have complex needs and typically need much more space than people are providing them.

In reality, animal care ranking systems that actually look at what an animal needs to thrive (we use something called the Emode Pet Score), rate the most commonly kept reptiles like crested geckos, corn snakes, ball pythons, and bearded dragons as difficult or extreme to care for. That means it’s unrealistic or almost impossible to provide appropriate care that meets their needs in captivity. And yet these animals are being kept as pets.

Animals suffer when their complex needs aren’t met

Amy: So because so many animals are being sold to people who can’t adequately care for them, we now have hundreds of thousands of wild animals who are suffering as pets.

According to World Animal Protection, there were about 1.4 million exotic pets being kept in Canada in 2019.

75% of pet snakes, lizards, and tortoises die within their first year in a new home. We know they experience a lot of suffering before they actually die.

Releasing unwanted exotic animals is a welfare and conservation issue

Amy: Some people who can’t care for their exotic pets even release them into the wild, which is harmful for that individual animal’s wellbeing.

And also, released animals become invasive species that are dangerous for our local wildlife populations and for our environment, such as red eared slider turtles.

So it’s really important that people learn about what exotic animals really need so that we can stop the flow of wildlife into homes where their needs can’t be met; move away from breeding exotic animals; and make sure we’re keeping wild animals in the wild.

Breeding vs. capturing wild animals

Chantelle: Now that we have an idea of why this issue is so important, I’d like to share an overview of what this industry actually looks like in Canada.

When we’re looking at exotic pets, there are two ways that animals are being brought into the market to be sold:

- The first is they are captured from the wild and imported.

- The second is that they’re bred in captivity.

About half of reptiles in the wildlife trade are wild caught according to World Animal Protection. Those figures may be higher for certain species of other types of animals that are difficult to breed in captivity

There are welfare issues for both of these methods.

Problems with capturing animals for the exotic pet trade

Chantelle: More than half of captured wild animals don’t survive transport. They’re being kept in these very small cages to be brought over and it’s really difficult to check on them during transport. Two thirds of African grey parrots that have been poached from the wild die in transit

Taking animals from their homes also threatens wild populations of those species. As many as 21% of endangered wild African grey parrots are taken from the wild each year for the pet trade. Those are already an endangered species in the wild.

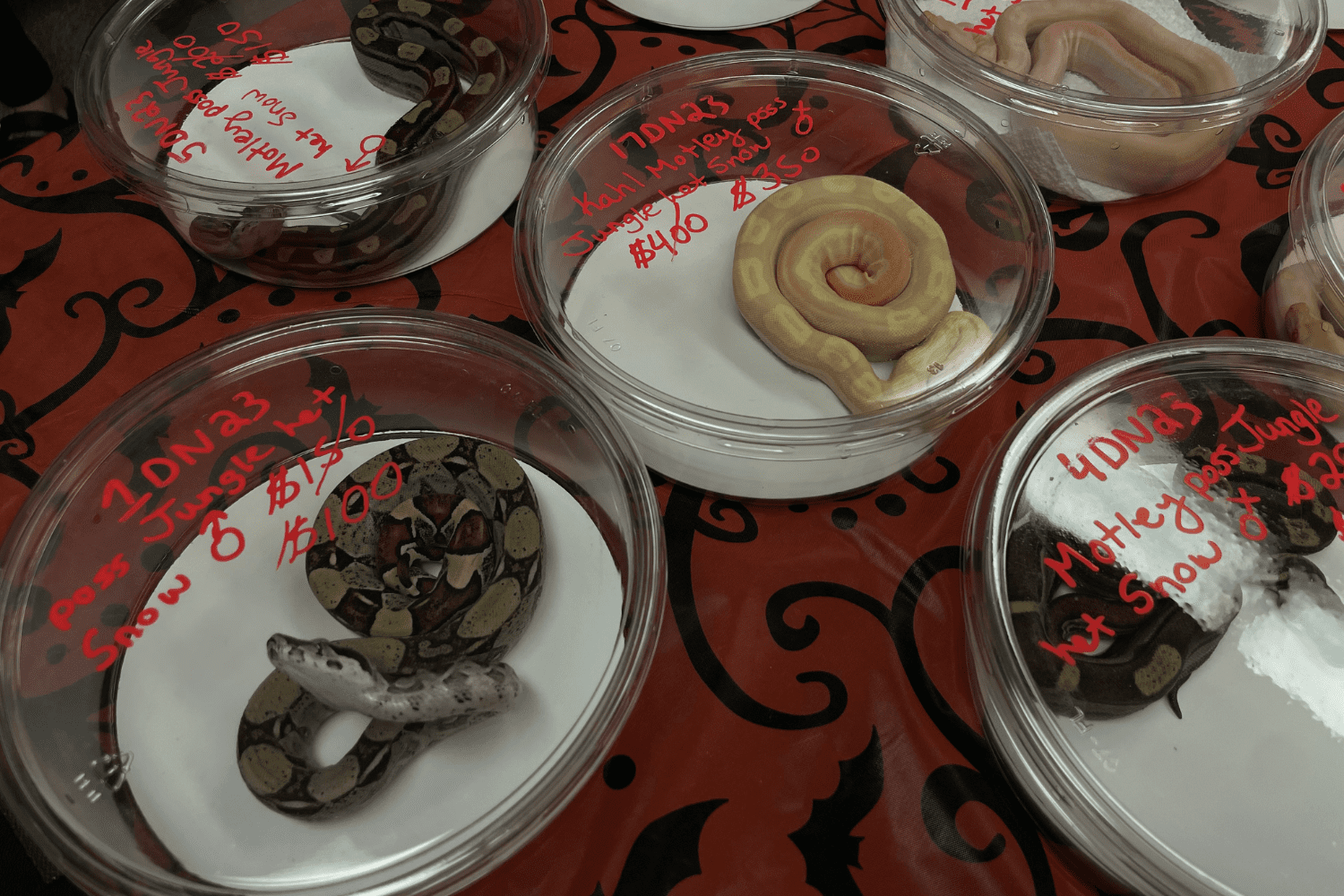

Problems with breeding exotic pets in captivity

Chantelle: Meanwhile, animals that are bred in captivity are often housed in small, basic enclosures because people who are really engaging in captive breeding to make a profit are breeding a lot of animals at once. That simple kind of housing makes it a lot easier to feed the animals, clean their cages, and monitor how they are doing.

Breeders will often keep animals in their home without a storefront, so the public has no way of really seeing what’s happening with those animals.

In B.C., as long as a species of animal isn’t prohibited under the Controlled Alien Species list and is under a certain size (snakes under three metres or lizards under two metres), basically anyone can breed those animals without a permit.

Two major problems with that model are:

- A lack of transparency. The public has very little way of knowing what’s going on and what the conditions are for the animals.

- A lack of regulation. Breeders aren’t being monitored, and there’s not really enforcement happening because someone would need to make a complaint; and who is there to see what’s going on to make a complaint?

Some breeders will also selectively breed for certain traits, like more unique colours and patterns, and that selective breeding can lead to neurological disorders that can have an impact on the animal’s wellbeing.

One example is ball pythons. Ball pythons with the spider gene, which is a genetic mutation that causes a spider web or a splatter pattern on the back of the snake, which some people consider a desirable trait, have the same mutation that causes a condition called wobble head syndrome.

That can make it hard for the snakes to move or feed properly. So depending on the severity of the condition, a snake might have a slight head tilt or they might flip their head upside down and not really realize and just kind of leave it there. They might not be able to move in a straight line. They might not be able to do things that they need to do to hunt and feed on their own, like strike and constrict.

Amy: And you know, this is a very specific thing that happens, but when we think of it on a broad scale, we’re also just facing breeders who breed animals just for volume and they’re not keeping animals in the space that they deserve.

So while we may have some of these cases that are problematic of these kind of genetic abnormalities, when exotic animals are being bred, they generally do not have housing that meets their needs.

How exotic animals are sold

Chantelle: After animals are either bred or imported, they’re sold through a variety of methods.

Selling exotic animals in pet stores

Chantelle: First there are pet stores. If you’ve been into a pet store that sells exotic pets, you’ve likely seen them stacked in a section in quite small cages. They may have spaces to hide, but they’re generally in full view of humans and other animals, which can be very stressful for them, especially for solitary species.

The stores are typically fairly bright during the day when they’re open, and a lot of these animals are nocturnal so their sleeping patterns can be disrupted.

There might be someone on staff who has knowledge about the needs of different exotic animals, but when a store sells such a wide variety of species, it’s unlikely that they have someone on shift who’s knowledgeable about every species all of the time.

Exotic pet fairs and expos

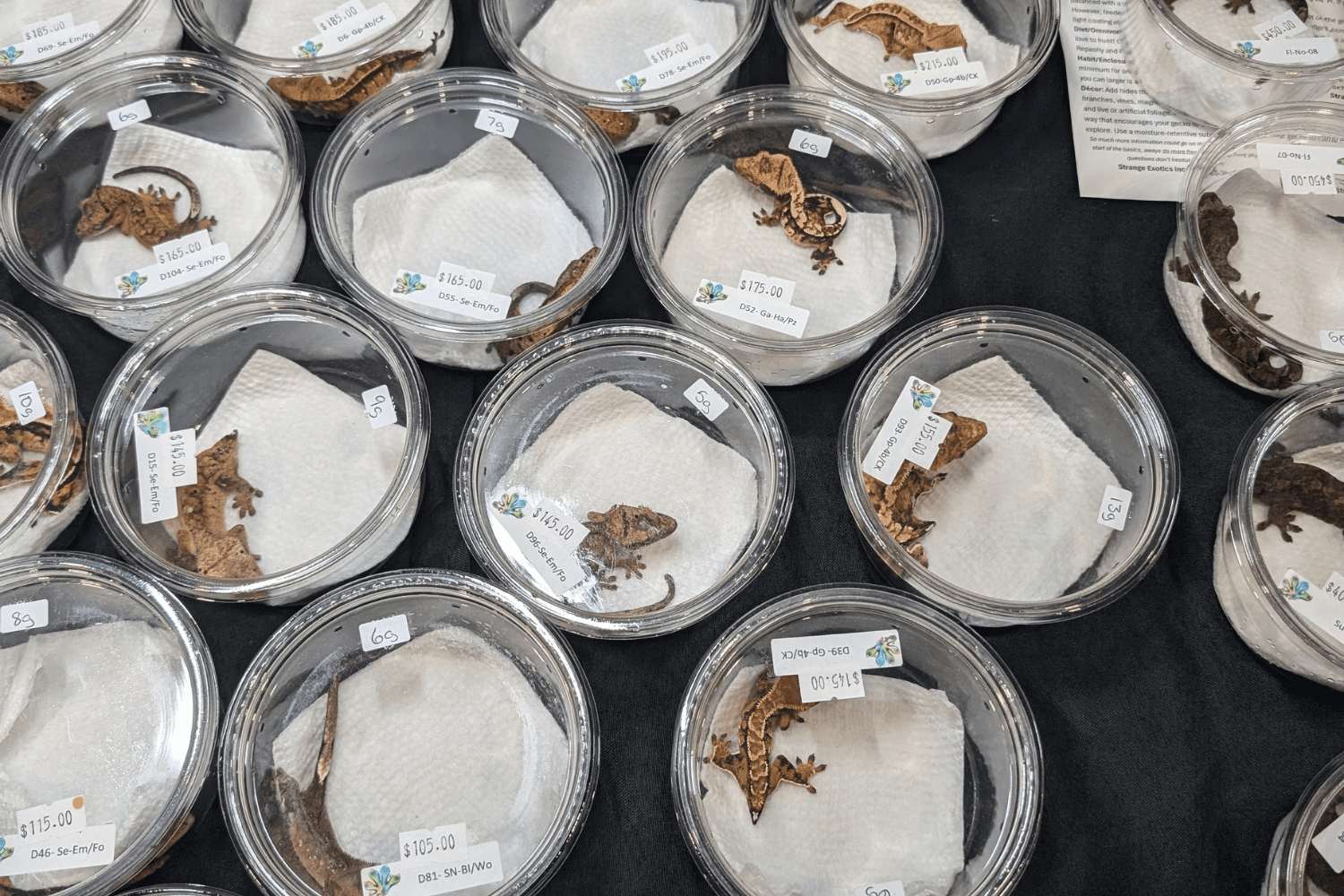

Chantelle: There are also exotic pet expos. These are generally people selling animals with more specialized knowledge, but there are still pets that are difficult to care for being sold as beginner pets with misleading information.

For instance, one of our colleagues was told by a seller at a pet show that a snake could be kept in an opaque container, when we know that they need specialized terrariums with temperature control, they need space to fully stretch out. They need enrichment items and substrate.

Also at these shows, pets are transported around during the day. They’re sold in very small containers, even takeout containers.

Even though there are rules that are supposed to limit how many people can handle the animals, it doesn’t appear those rules are strictly enforced. There have been children handling reptiles in these crowded rooms.

Imagine if a child were to drop, say, a small lizard at an expo when there’s a bunch of people walking around; that could very quickly become a dangerous situation for the animal.

Selling exotic animals online

Chantelle: There’s also animals that are sold online. That involves shipping the animals from a seller’s location, usually also in small containers with temperature packs.

It’s more difficult to tell how an animal is being kept and transported this way. Not all sellers have the same level of care in keeping animals safe during transport. Even though even the best ways of transporting them are not ideal conditions for the animal, there are ones that are significantly worse.

Amy: We think about transport and the animals who die in transport, and these are animals that have been purchased that have kind of like a value assigned to them; they’re still not being transported in ways that are good for the animal.

And we think about the animals that are at a breeder’s house that have not been purchased yet and don’t have the same kind of value attributed to them, you kind of wonder like how many animals are dying in care. We just don’t have any data or numbers on that.

There’s no requirements on registering. For the majority of these animals, there’s no reason for a breeder to disclose anything that’s happening in their home.

We’ve heard from breeders about some of their housing situations and they do not sound like a situation I would want to be in as an animal, that’s for sure.

Chantelle: And regardless of the level of care that the breeder takes, the animals are still typically shipped in a way that it would be either difficult or impossible to monitor how they’re doing while they’re in transit.

They’re put in a box and they’re shipped, and you see how they’re doing when they’re at their original locationand you see how they’re doing at the end destination, but you can’t see how they’re doing in transit.

Animals surviving doesn’t mean they are thriving

There are about 1.4 million exotic pets being kept in Canada as of the most recent count we could find, and again, it’s very difficult to meet the needs of these animals in captivity. Most of them do sadly die far before the end of their natural lifespan.

Even if their basic needs to survive are being met, that doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re getting what they need to thrive.

Rescues struggling to keep up

Amy: We have rescues in Canada and one rescue shares on their website that they have 350 animals in their care. You think about cat or dog rescues, and if you heard the number 350, you would not think that someone could adequately care for all of those cats and dogs.

And when we’re thinking about exotic species, each individual species needs different care and different food and different housing and warmth. And so even thinking about any kind of operation that’s housing this volume of animals is likely going to be challenged to be able to do that.

I personally just feel really frustrated when I’m hearing about these things because it’s hard to imagine a rescue is trying to do their best because these are unwanted animals. They’re sort of like the disposal of an exotic pet industry.

But meanwhile, some organizations are bringing them into classrooms and having people handle them and inviting kids in to handle them as well. And in a way that’s sort of instilling an interest in keeping these animals as pets, even if unintentionally.

And realistically, a rescue does not want to house so many animals. They do want individuals caring for them. And so you end up in this really weird place where just by the exotic pet industry existing, there’s a whole series of ethical dilemmas that come out of it, and in every case, the animals lose.

Laws around exotic pets

Amy: The next thing I’m hoping to cover is the laws around keeping, breeding, and importing exotic animals.

We’ve spoken in depth about captivity laws in Canada. You can find a longer discussion about this topic if you go back to our episode called Animal captivity laws with Rob Laidlaw, the founder of the organization Zoocheck.

To give a brief overview, the laws in this area are a lot like the other laws we’ve talked about on our show. There’s a patchwork of federal and province-specific laws that differ across the country, and then municipal bylaws that branch out even further.

Federal laws around the wildlife trade

Amy: The main thing we look at when we’re talking about federal laws around exotic animals is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

That’s an international agreement that Canada is a signatory to.

CITES is designed to protect endangered species by banning or limiting the international trade of plants and animals and their parts that are endangered. There’s different levels of protection depending on how at risk the species is. That’s fairly limited.

Canada delivers on our commitments to the CITES agreement through something called the Wild Animal and Plant Protection and Regulation of International and Interprovincial Trade Act (WAPPRIITA).

That act controls the import of CITES listed species, plus other species whose trade is banned under other laws like the country of origin or provincial laws.

And really there’s so many exemptions to that, that it’s not a super helpful law when it comes to people keeping wild animals as pets. It really is more around protecting animals in other countries and their parts.

Provincial laws around exotic animals in captivity

Amy: Most of the responsibility for captive wildlife is dedicated to the provinces, and the laws really vary from province to province.

Here in B.C., the keeping breeding transport and release of exotic animals are regulated under the Controlled Alien Species regulation (CAS), and that’s part of the Wildlife Act.

More broadly, under this regulation, we have a list of specific animals that are considered not native to the province, and that pose a risk to the health or safety of people, property, wildlife, or wildlife habitat.

However, once again, this is a short list. And it’s mostly focused on risk to the public and native ecosystems, and it’s not really thinking about the exotic animals and the risks they face.

The CAS tries to list all of the animals that are not allowed. We have so many species in the world, and new species that are being discovered all the time, so this kind of list leaves many gaps.

For instance, kangaroos aren’t listed even though they’re not native to B.C. and they’re considered an invasive species in other places such as New Zealand.

What we know is more effective and what VHS and other organizations have been advocating for is a positive list approach, where only the animals that are allowed to be kept are listed based on knowledge about what species are suitable and can actually thrive under human care in B.C.

Unfortunately, while we know that this would be really effective in improving animal welfare, it’s been very difficult to get the ear of the government to have any kind of weight put towards this policy option.

It’s one of those situations where best practice and good policy is kind of put aside because it involves bureaucracy and it impacts people. And if something impacts people, they have to do an assessment. And so sometimes it’s easier to just leave things as they are.

Municipal laws around exotic animals

Amy: There’s so many gaps and inconsistencies at the federal and provincial level, so municipal or regional bylaws try to fill the gaps with their own rules.

While this is nice on a small scale and we really support and encourage those municipalities, there are also some big challenges because it’s such a small scale.

Some of those challenges is that city or town councils don’t have as many resources to find and hire people with expertise to develop these laws.

There’s 161 municipalities in B.C. That’s 161 local governments trying to find experts who understand what reptiles need and putting their limited time and budget toward developing bylaws that meet those needs.

Whereas at the provincial or federal government level, they have much more resources and experts who could develop a comprehensive legislation that would just cover a large land area.

Also, when the bylaws cover a small area, individuals will just move a couple towns over and continue what they’re doing. We’ve seen that happen with breeders quite often, where they’ll just move to an unincorporated area.

So as much as we can appreciate bylaws, things really do need to be done at the provincial and federal level.

How are exotic animal laws enforced?

Chantelle: Because the legislation around transporting exotic animals is so complicated, there are a lot of problems with enforcement, even when there are laws.

You have these laws with long lists of species that aren’t allowed into the country or into the province, and they’re coming through border checkpoints where the staff at these checkpoints are not animal experts. It’s almost an impossible ask to have these enforcement agents be able to identify each species that’s coming in and whether or not they’re allowed.

Gaps in documents around animals imported to Canada

Chantelle: World Animal Protection looked at 1.8 million wild animals that were imported into Canada from 2014 to 2020. About half of those animals were imported for the pet trade.

They found that the records around the animals that were coming in had huge data gaps. 84% of animals didn’t have their species named. Rhere was no information available about the animal’s background if they were caught in the wild or bred in captivity.

It’s very difficult to even know if these laws were being followed at the time.

Their organization also noted that since there’s such a convoluted list of which department is responsible for which animals, that almost all species imported for the pet trade aren’t really being looked at.

How you can help

Amy: The first step to solving a problem is to know what the problem is and to have all the information on it, and then we can start to take action.

Make exotic animals a part of your conversations

Amy: The most important thing that you can do as an individual is really encourage the people around you not to buy exotic animals from sellers or breeders.

That’s easy to say, but hard to do because you don’t even know someone’s considering buying an exotic animal until they get one, and then you’re surprised by it.

So it’s also just finding opportunities in conversation to highlight some of these challenges and have it be a whole mindset where animals are not being brought or traded in private operations.

Encourage adopting, not shopping

Amy: Also, if you know someone who has the time, resources, capacity, and desire to take in an exotic animal, encourage them to adopt a rescue animal.

As I was mentioning earlier, one impact of so many animals being sold to people who don’t have the resources is that when people go to surrender their animals, there’s just so little capacity at legitimate rescue organizations to take those animals in.

And when we’re saying legitimate rescues, we mean organizations that are making decisions based on what’s in the best interest of the animals in their care.

Share information about the exotic pet trade

Amy: You can also share information about this on social media and in local community groups. The VHS has been working on an educational campaign on social media the past few months that you can share the realities of keeping exotic pets, what their needs are, the welfare concerns, and what the impacts are on conservation, the animals’ health, and public health risks.

You can find a carousel of posts to share on Instagram and Facebook, and a link to our Blue Sky account.

Speak with pet store managers

Amy: One other way that you can kind of think about taking action is talking to pet stores.

One thing I did when I moved to a new town: I was checking out different pets stores where I would trying to find a place to buy food for my dog.

One of the pet stores was selling betta fishes. And I shared some concerns around that and they shared with me that there’s demand in the town for it. They felt that it was an appropriate animal to keep in captivity.

We kind of went back and forth on it and I said, I would love to buy pet food from here, but I am not comfortable doing so with you selling betta fishes.

I gave them my info and said like, get in touch if you ever decide to stop selling exotic animals and I’d be happy to make your store my primary pet store.

So this is something you can definitely do with smaller scale stores. It is harder with stores that are chains because they may not have as much decision making power.

But you can always ask to speak to a manager and understand what their discretion is and what their choices are.

Approach with curiosity and compassion

Amy: Most of all, you can have some grace when you do encounter people who have exotic animals as pets. Shame and guilt are never the way to change someone’s mind or change someone’s behaviour. They just don’t work and they kind of do the opposite. People dig in their heels and say, no, I’m not changing, I’m not doing anything different. I’m right.

When having conversations about exotic pets or with people who have different thoughts than you on it, it’s so important to genuinely be curious, to be kind, to ask questions, to share your own gaps in knowledge and to really share from a place of care and love and concern.

And I think you can go a long way in the long term of shifting someone’s mindset if you come from that perspective. And also gently say, you know, “I’d love to research this more together. I don’t know a lot about this animal. You seem to know a lot, but I’m really keen to get a sense of what they need and what their environment is like.”

And if you do the research together, maybe there’s a chance that they’ll appreciate your interest and curiosity. And if they find out information about like, oh, they should have a much bigger tank or something like that, then they’ll be more likely to adopt that practice.

Certainly, I would say you can always have a bigger tank than what you have and always have more spaces to hide. Always have, more ability to stretch out, move around.

Work toward a common goal

Chantelle: Especially for something like this, the people who are interested in taking animals into their home are generally people who have like an interest and a love for animals. So we all are coming at this from the same place where we want what’s best for animals. And some people just don’t have the knowledge and the resources to know what is best.

We had a quote on our social media recently, which is from an exotic animal vet named Dr. Alix Wilson, who had said, “Every day I see birds whose owners love them dearly, but aren’t taking proper care of them. They simply don’t know what they’re taking on.” And that was regarding treating grey parrots.

There’s so many people who are taking these animals into their homes and they don’t know what they’re getting into. The length of the life that the animal has naturally, it’s a enormous commitment of time, of resources, of money to be able to take these animals.

Especially buying them from a breeder or a seller. These animals don’t need to be taken out of the wild or bred in captivity.

Next episode

Please join us again next month as World Animal Protection joins us to discuss their Animal Protection Index and how Canada’s federal animal laws and regulations stack up against other countries on the world stage..