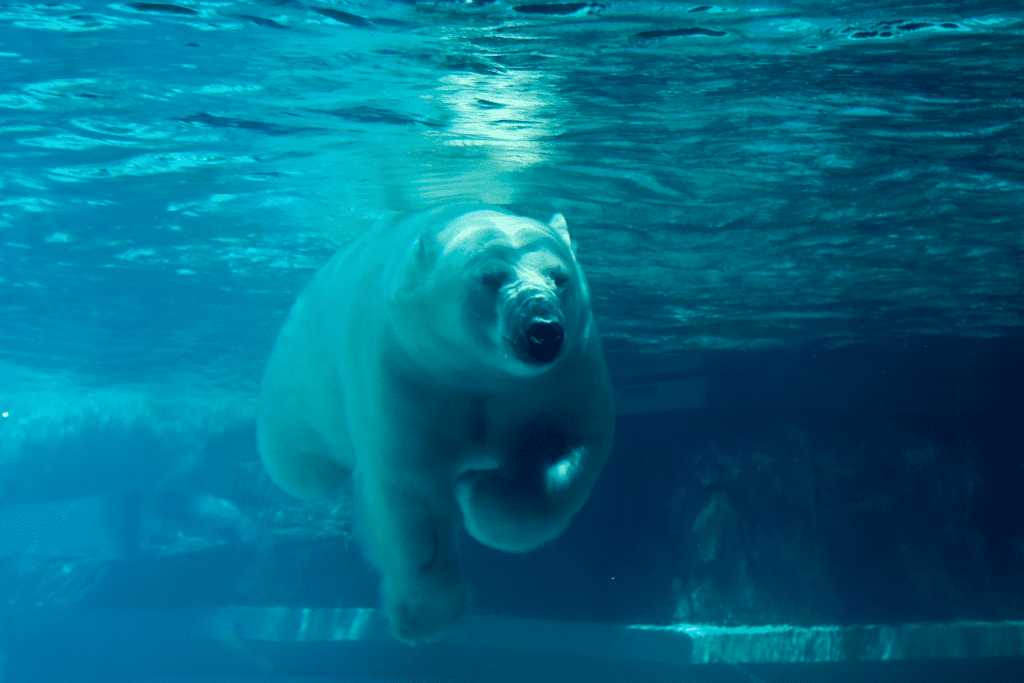

Wild animals are suffering in captivity.

Keeping wild animals for public display, entertainment, or as pets deprives them of the ability to freely engage in instinctual behaviours in their natural environment.

Even when bred in captivity, exotic animals retain the behavioural and biological needs that they would have in the wild.

They cannot be considered domesticated and they can suffer if they are confined in unnatural environments.

Quick actions for animals in captivity

Take action to help protect animals in captivity! These quick actions take less than 2 minutes to advocate for meaningful change..

Exotic animals: wildlife, not pets

Exotic, non-domesticated animals are being caught, bred, and sold across Canada as part of the…

Open letter: B.C.’s wild and exotic animal captivity rules due for update

VHS and residents from across B.C. and Canada call for better protections for wild and…

Protect wild, exotic animals in captivity: Petition

Wild, exotic animals suffer in captivity Zoos and aquariums cannot replicate the size and complexity…

Areas of focus

For decades, the Vancouver Humane Society has advocated to protect wild and exotic animals from suffering in captivity. Read about the history of this work.

Latest updates

Stay informed on the latest issues affecting animals in captivity. Explore recent updates, actions, blog posts, and media to learn how you can help advocate for their protection.

Captive animal deaths reignite calls for urgent protections

Port Moody could soon ban mobile petting zoos

Exotic animals: wildlife, not pets

Podcast: Jenga the giraffe dies at the Greater Vancouver Zoo (The Early Edition)

Conservationists call for greater transparency, systemic review of Calgary Zoo

DONATE TODAY TO SEE AN END TO KEEPING WILD ANIMALS IN CAPTIVITY!

In the media

Follow key moments in the fight against animal suffering in captivity. This timeline highlights major news, developments, and advocacy efforts shaping the conversation on animal welfare.

Past actions for animals in captivity

Explore past actions for animals in captivity and the impact they’ve made.

Update: Speaking up for sled dogs and wild animals in captivity

This summer, the VHS ramped up calls for changes to B.C.’s regulations on two…

Call on your B.C. MLA to act for sled dogs and wild animals in captivity

UpdateThis action has now ended. Thank you to the 452 advocates who signed up to…